As delegates from around the world gathered in Baku, Azerbaijan, for the 2024 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29), the stage was set for another round of pledges, promises, and- if recent history is a guide – disappointments.

While leaders from the Global North polished their speeches about ambitious green transitions, the Global South braced for more empty rhetoric. The chasm between rich and poor nations has widened, and this year’s conference may serve as the tipping point for developing countries that are tired of bearing the brunt of climate change without the resources or respect they deserve.

The broken promises of climate finance

The roots of this frustration are clear. In 2009, wealthy nations pledged $100 billion per year in climate finance by 2020. Fast forward to 2024, and this target has yet to be met. To add insult to injury, the amount promised is widely acknowledged as insufficient. Developing countries,including India and much of Africa, have repeatedly argued that at least $1.3 trillion annually is needed to address their adaptation and mitigation challenges effectively.

“Climate finance is not charity; it is an obligation,” India’s environment minister said recently,calling out wealthier nations for their failure to deliver on commitments. His sentiment is echoed across the Global South, where countries are struggling to finance renewable energy projects,coastal defenses, and drought-resistant agriculture.

Meanwhile, African nations are particularly aggrieved. Despite being among the hardest hit by climate change (caused mainly by the highly developed Global North), the continent receives just 3% of global climate finance. The inequity is glaring. Mozambique, Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo for instance, have endured multiple cyclones and exceptional weather catastrophes in recent years, displacing thousands and wreaking economic havoc. Yet,funds to help these nations adapt and recover are scarce, leaving them trapped in a vicious circle of destruction and poverty.

Privatizing responsibility: A dangerous trend

One of the most contentious debates at COP29 is the increasing emphasis on private investment in climate finance. While developed nations celebrate private capital as a game-changer, countries like India see it as a cop-out. “Shifting the burden to private investors absolves governments of accountability,” said a negotiator from the G77 bloc – group of developing countries in the UN. Critics argue that private finance is often tied to market returns, which sidelines the poorest and most vulnerable communities.

Consider the case of renewable energy in sub-Saharan Africa. While private firms invest in solar and wind projects, these initiatives are often geared toward urban areas or export markets,bypassing the rural communities most in need. The result? A patchwork of progress that leaves millions in the dark—literally and figuratively.

The fossil-fuel elephant in the room

Adding fuel to the fire – pun intended – is the presence of over 1,700 fossil fuel lobbyists at COP29, a record high for any climate conference. Their influence looms large over negotiations, with activists accusing them of undermining efforts to phase out coal, oil, and gas.

The irony is hard to miss: while small island nations plead for immediate action to prevent rising sea levels from swallowing their homes, fossil fuel interests are busy ensuring that transitions remain slow and their profits remain high. “It’s like inviting arsonists to a fire safety conference,” quipped one frustrated delegate.

G20 hypocrisy on display

While developing countries grapple with existential threats, the G20 nations – responsible for 75% of global emissions – continue to fall short on their climate commitments. A recent report by the Council on Energy, Environment, and Water (CEEW) revealed glaring gaps in emission reduction policies across these major economies.

Take the United States, for example. Despite its Inflation Reduction Act, which promises significant investments in clean energy, the country has yet to align its actions with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C target. Similarly, European nations have struggled to reconcile their green ambitions with growing energy demands and political push back.

The loss and damage fund: A test of good faith

One of the few bright spots of last year’s COP28 was the establishment of a Loss and Damage Fund, designed to compensate vulnerable nations for climate-related destruction. However,implementation remains stalled. With no operational framework or guaranteed funding, the initiative risks becoming another hollow promise.

For countries like Pakistan, which suffered catastrophic floods in 2022 that displaced over 30 million people, the stakes couldn’t be higher. “This fund is not a luxury; it’s a necessity,” said Pakistan’s climate minister. Yet, without swift action, the fund could end up as another bureaucratic black hole.

Statistical realities and stark contrasts

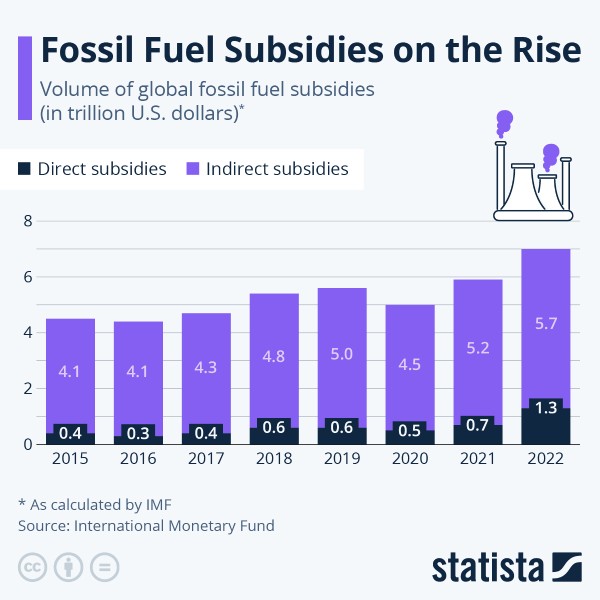

The numbers tell a damning story. Africa will pay $163 billion in debt service in 2024 – money that could have been used for climate adaptation. Meanwhile, the fossil fuel industry rakes in trillions in profits annually, with subsidies from governments adding insult to injury. In 2022 alone, global fossil fuel subsidies hit a staggering $1 trillion, dwarfing investments in renewable energy.

These disparities are not just economic; they are moral. How can rich nations preach sustainability while continuing to finance coal plants abroad? How can they demand emissions reductions from countries like India, whose per capita emissions are a fraction of those in the West?

A call for a new paradigm

As COP29 concluded, the question is not just whether rich nations will listen but whether they will act. The Global South is no longer content to be a passive recipient of aid. Countries like Brazil, South Africa, and Indonesia are pushing for a more equitable global climate architecture – one that includes debt relief, fair trade policies, and technology transfers.

Even Pope Francis weighed in recently, calling for “a bold and creative rethinking of the global financial system.” His words resonate with leaders in Africa, where debt servicing often outweighs spending on health and education.

“We’re asking for fairness”

The COP29 ended with more delays and diluted commitments. It is not just a failure of diplomacy but a betrayal of humanity. The climate crisis is a global problem that requires global solutions, yet the burden remains unevenly distributed. As one African delegate put it, “We’re not asking for favors; we’re asking for fairness”.

Perhaps the most poignant reminder came from a young activist in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, who held a sign that read: “You broke it. You fix it.” The message is clear. It’s time for the Global North to put its money where its mouth is – or risk losing what little credibility it has left. After all, In the words of another activist’s poignant sign, “The house is on fire.” Let’s hope Baku doesn’t become the place where the fire spreads unchecked.

Author

Moussa Ibrahim, Executive Secretary of the African Legacy Foundation, Johannesburg