It consists in the idea that a public, on average knowing almost nothing, can choose leaders in popularity contests among provincial lawyers who know little more and are required to know nothing, except how to get elected.

In a democracy, this ignorance is both a protected quality, like motherhood and a valued resource. By common consent, the ruled do not look too closely at the mentality of elected rulers, and the rulers speak solemnly of the wisdom of the people, who have none. Reporters will ask, “Senator, what are your views on Afghanistan?” but never, “Senator, where is Afghanistan?” or “Can you spell Afghanistan?”

To plumb the depths of democratic puzzlement, we might, by means of polls, ask how many voters can name three cities in China apart from Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. Or how many can name even those cities. Or how many know even one date in Chinese history, or can name a single province. Yet they know that China is perfectly dreadful and dangerous.

Ask what countries border on the Caspian or Black Sea. Or, seriously, how many have ever heard of the Caspian. In today’s politics, these are not quiz-show trivia but influence Washington’s choice of our next war.

See how many have heard of the Minsk Accords. If they have not, they lack a hamster’s grasp of the Ukraine war. What they think they know probably comes through CNN and MSNBC, assiduous hawkers of the not so.

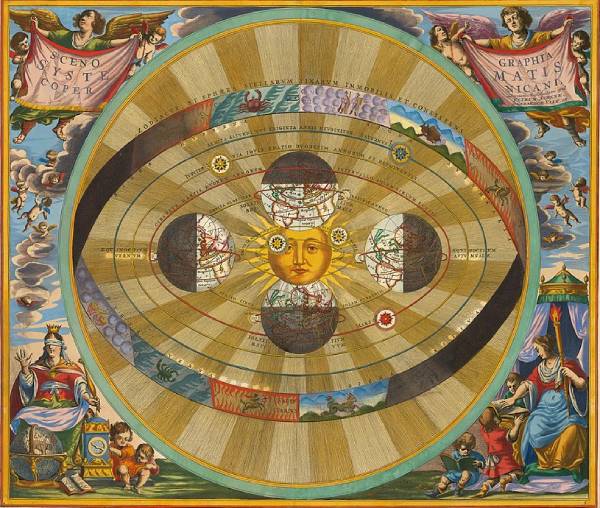

Gallup: Twenty-one percent of Americans believe the sun revolves around the earth.

Fifty-four percent of Americans read below the sixth-grade level.

A good bet is that the lower third in intelligence of the population know nothing at all of international affairs and exceedingly little of national. Given the appallingly poor schools in the cities, another good bet is that the proportion of blacks cognizant of international geography or politics is vanishingly low. Since Latin American cardiac surgeons and system programmers do not swim the Rio Bravo to pick oranges in Florida, the Hispanic percentage is unlikely to be greatly better. Taken as wholes, none of these three groups is remotely qualified to vote.

Representative Sheila Jackson Lee (D-Texas) stunned attendees at a high school solar eclipse event Monday by claiming the rock-solid moon is a “planet” that is “made up mostly of gases” — before adding she still wants to be “first in line” to learn how to live there.

I suggest sending her. She is the former top Democrat on the House Science Committee’s space subcommittee.

While little more than a third of respondents (36 percent) could name all three branches of the U.S. government, just as many (35 percent) could not name a single one.

In reading, 628 Patterson High School students took the test. Out of those students, 484 of them, or 77%, tested at an elementary school reading level. That includes 71 high school students who were reading at a kindergarten level and 88 students reading at a first-grade level. Another 45 were reading at a second-grade level. Just 12 students tested at Patterson High School, were reading at grade level, which comes out to just 1.9%.

While people who read political columns online are likely of intelligence above the average, i wonder how many who rail against capitalism, socialism, fascism, racism, and terrorism can define the words.

I recently checked the bios of the members of the House committee on China to see how many read, write, or speak Chinese. None. Thus do we make policy regarding the most important foreign country on the planet.

A friend, a former US Senator, once estimated, dead serious, that ninety percent of the Senate doesn’t know where Myan Mar is. If you and I, dear reader, do not know this, it probably doesn’t matter. The Senate engages in foreign policy.

It is important to note that intelligence does not by itself confer the capacity to vote. I know people way into the upper percentiles who do not have the time or the interest to worry about foreign policy, for example. There are engineers, neurosurgeons, mathematicians, journalists, musicians and artists, whose minds just don’t run in political directions, especially involving obscure countries on the other side of the world. Neurosurgeons have families who merit attention, journals to read to keep up with their fields, perhaps a hobby or two, and don’t have much left over to worry about a new Russian pipeline across Mongolia, wherever that is.

People I have met of IQ 190 or better, maybe four (of whom I assuredly am not one), have had the memory and analytical capacity to, I think, approximate an understanding of politics, history, and so on. These people are so rare as to be almost nonexistent. The rest of us at best can know bits and pieces.

For example, my knowledge of Caucasian politics consists entirely in the fact that Washington wants to put military bases in Georgia to help surround Russia. I am blankly ignorant of Congressional and state politics, agricultural policy, or much about what Blackrock is doing around the world. There is too much to know, and too little wit to know it with.

If we ignore exceptions and degrees, the public can be regarded as a vast semi-comatose polyp that knows only whether it is comfortable or cold and wet and has enough to eat. If the economy is good, people will vote for incumbents, whether these have any responsibility for the prosperity or not. If wars can be fought without inconveniencing them, in places not actually within their visual horizon, they will pay scant attention. They will not concern themselves with education as long as their children get good grades, however unrelated to anything learned. Their interests are local, though they can be stirred up over this football team or that, this Trump or that Biden, or morality plays about police brutality or the righteous heroism of Ukrainians.

Taking into account the aforementioned poor education, controlled media, and American anti-intellectualism–Americans seem to dislike the obviously intelligent–and you have a polity utterly incapable of anything approaching functional democracy. Rev the people up over the Superbowl or morality tales about the Ukraine or Russia and they will do anything desired. Roll over. Bark. Beg. Nothing to it.

Author

Fred Reed, a keyboard mercenary with a disorganized past, has worked on staff for Army Times, The Washingtonian, Soldier of Fortune, Federal Computer Week, and The Washington Times. He has been published in Playboy, Soldier of Fortune, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Harper's, National Review, Signal, Air&Space, and suchlike. He has worked as a police writer, technology editor, military specialist, and authority on mercenary soldiers.