Prior to the Industrial Revolution, most humans were engaged in agriculture. Our relationship with nature was immediate. Within just a few generations, however, for many people across the world, their link with the land has been severed.

Food now arrives pre-packaged (often precooked), preserved with chemicals and contains harmful pesticides, micro-plastics, hormones and/or various other contaminants. We are also being served a narrower menu of high-calorie food with lower nutrient content.

It is clear that there is something fundamentally wrong with how modern food is produced.

Although, there are various stages between farm and fork, not least modern food processing practices, which is a story in itself, a key part of the problem lies with agriculture.

Today, many farmers are trapped on chemical and biotech treadmills. They have been encouraged and coerced into using a range of costly off-farm inputs, from synthetic fertilisers and corporate-manufactured seeds to a wide array of weedicides and pesticides.

With the industrialisation of agriculture, many poor, smallholder farmers have been deskilled and placed into vulnerable positions. Traditional knowledge has been undermined, overwhelmed or has survived only in fragments.

Writing in the Journal of South Asian Studies in 2017, Marika Vicziany and Jagjit Plahein state that farmers have for millennia taken measures to manage drought, grow cereals with long stalks that can be used as fodder, engage in cropping practices that promote biodiversity, ethno-engineer soil and water conservation and make use of collective sharing systems.

Farmers knew their micro-environment, so they could plant crops that mature at different times, thereby facilitating more rapid crop rotation without exhausting the soil.

Experimentation and innovation were key. Two terms modern agritech/agribusiness corporations lay claim to, but something farmers have been doing for generations.

Many farmers also used ‘insect equilibrium’ and their knowledge of which insects kill crop-predator pests. Food and policy analyst Devinder Sharma says he has met women in India who can identify 110 non-vegetarian and 60 vegetarian insects.

Complex, highly beneficial traditional knowledge systems and on-farm ecological practices are being eroded as farmers lose control over their productive means and become dependent on proprietary products, including commodified corporate knowledge.

as farmers lose control over their productive means and become dependent on proprietary products, including commodified corporate knowledge.

Farmers in places like the Netherlands are now being blamed for harming the environment due to carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide emissions. Although Dutch farmers are taking flak, what we are also seeing is an attack on large feed and meat producers. There are not many small farms left in the Netherlands and most animal farms are concentrated feeding operations.

The Netherlands’ farming sector is highly livestock intensive and there seems to be a policy to reduce the size of the meat industry in that country. Farmers have been told to get out of farming or shift to growing crops.

Instead of the authorities facilitating a gradual shift towards organic, agroecological agriculture and attract a new generation to the sector, farmers are in danger of being displaced.

But Dutch farmers are not the only ones in the firing line. Farmers in other European nations are also protesting because various policies make it increasingly difficult for them to make a living.

There seems to be a concerted effort to make farming financially non-viable for many farmers and remove them from their land. The farmer protests in Europe follow in the wake of massive resistance by Indian farmers against corporate-backed legislation that would have seen an accelerated drive to push many already financially distressed farmers out of farming.

Farmer Bill

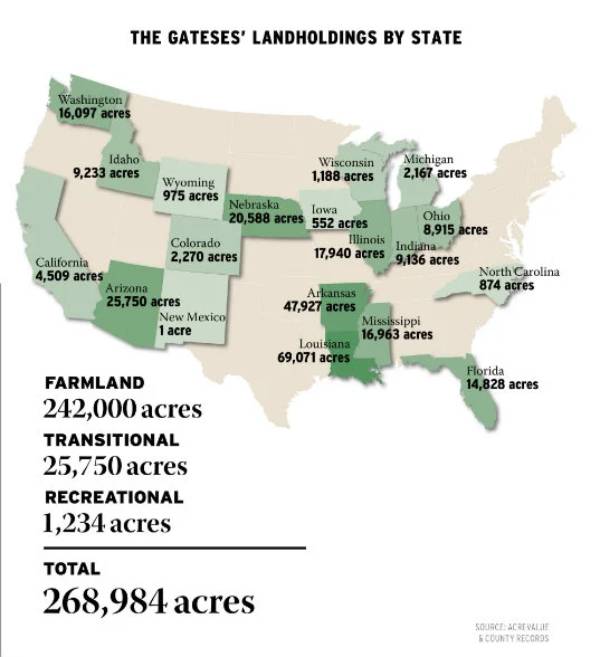

The biggest owner of private farmland in the US – Bill Gates – has a vision for farming: a chemical-dependent, corporate-dependent, one-world agriculture (Ag One initiative) to facilitate the global supply chains of conglomerates. This initiative is side-lining indigenous knowledge and practices in favour of corporate knowledge and a further colonisation of global agriculture.

Gates’s corporatisation of smallholder agriculture is packaged in philanthropic terms – ‘helping’ farmers in places like Africa and India. It has not worked out well so far if we turn to the Gates-backed Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), established in 2006.

The first major evaluation of AGRA’s efforts to expand high-input agriculture in Africa found that – after 15 years – it had failed. With concerns being voiced over the use of hazardous pesticides, less than impressive yields, the privatisation of seeds, corporate dependency and farmer indebtedness, among other things, we can expect more of the same under the Ag One initiative.

But the ultimate high-tech vision for farming is farmerless farms largely overseen by driverless vehicles and AI-driven sensors and drones linked to cloud-based infrastructure. The likes of Microsoft will harvest field data on seeds, soil quality, historical crop yields, water management, weather patterns, land ownership, agronomic practices and the like.

Tech giants will control multi-billion-dollar data management markets that facilitate the needs of institutional land investors, agribusiness and monopolistic e-commerce platforms. Under the guise of ‘data-driven agriculture’, private corporations will be better placed to exploit farmers’ situations for their own ends.

With lab-based synthetic meat being promoted and attracting huge interest from investors, Gates and the agritech sector also envisage a largely ‘climate-friendly’ animal-free agriculture, which they claim will result in freeing up vast tracts of farmland (we can only speculate for what).

It remains to be seen just how energy-efficient, environment-friendly and health-friendly synthetic meat labs are once scaled up to industrial levels.

At the same time, industrial agriculture will use new technologies – minus farmers – and will still rely on and boost the use of fossil-fuel-dependent agrochemicals (with all the associated health and environmental problems) and remain focused on long-line supply chains, unnecessarily shipping food around the world.

A high-energy system reliant on the oil and gas that has fuelled the colonisation of the food system (‘globalisation’) by agribusiness conglomerates. Moreover, the new human-less on-farm technologies will be energy-intensive to run and will rely on environment-destroying extraction for finite resources like lithium, cobalt and other rare-earth elements to produce.

Low-energy agroecological approaches based on the principles and practices of localisation, local markets, authentic regenerative agriculture and proper soil management (which ensures effective and ecologically sound nitrogen and carbon storage) are key to ensuring genuine long-term sustainability in food production.

Many who belong to the agribusiness lobby have been drawing attention to Sri Lanka in an attempt to show organic farming can only lead to disaster. A transition to organics has to be gradual, not least because regenerating soil cannot occur overnight.

Regardless, the article ‘Sri Lanka Faces Food Crisis – No, It’s Not Due to Organic Farming’ that recently appeared on The Quint website reveals why that country really headed into crisis.

Great refusal

The neoliberal programme that took root in the 1980s has now reached a debt-bloated, inflationary impasse. In response, capitalism has embarked on a ‘great reset’ with transformative technology very much to the fore in the guise of a ‘4th Industrial Revolution’, promising a brave new tomorrow for all.

However, there are deep-seated concerns about how this technology could be used to monitor and control entire populations, especially as we are witnessing a brutal economic restructuring and increasing clampdowns on personal liberties. If neoliberalism promoted individualism, the ‘new normal’ demands strict compliance – individual freedom is said to pose a threat to ‘national security’, ‘public health’ or ‘safety’.

There is also concern about economic collapse, war and the exposure of a food system to energy price shocks, supply chain breakdowns and commodity market speculation.

In Mali in 2015, Nyeleni – the international movement for food sovereignty – released The Declaration of the International Forum for Agroecology.

Essential natural resources have been commodified, and rising production costs are driving us off the land. Farmers’ seeds are being stolen and sold back to us at exorbitant prices, bred as varieties that depend on costly, contaminating agrochemicals.”

It added:

Agroecology is political; it requires us to challenge and transform structures of power in society. We need to put the control of seeds, biodiversity, land and territories, waters, knowledge, culture and the commons in the hands of the peoples who feed the world.”

The Declaration made it clear that the prevailing capitalist food system had to be challenged and overcome.

In analysing the potential for challenging the capitalist order, Herbert Marcuse stated the following in his famous 1964 book One-Dimensional Man:

“A comfortable, smooth, reasonable, democratic unfreedom prevails in advanced industrial civilization, a token of technical progress.”

Today, we might say – an uncomfortable, unsmooth, unreasonable, undemocratic unfreedom prevails, a token of an emerging techno-dystopia.

Marcuse felt post-war mass culture had made people repressed and uncritical. They were a reflection of a one-dimensional system based on the consumption of commodities and the effects of modern culture and technology that served to dampen dissent.

The controlling nature of technology pervades all aspects of life today. But whether it involves farmers protests in Europe and India, the advancement of a political agroecology, truckers taking to the streets in Canada or ordinary people protesting against a rapidly advancing authoritarianism in Western societies, many people across the world know something is seriously amiss.

To borrow from Marcuse, we are seeing a ‘great refusal’ – people saying ‘no’ to multiple forms of repression and domination – tentacles of an economic system in crisis.

Author

Colin Todhunter specialises in development, food and agriculture and is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization in Montreal. You can read his “mini e-book”, Food, Dependency and Dispossession: Cultivating Resistance, here.