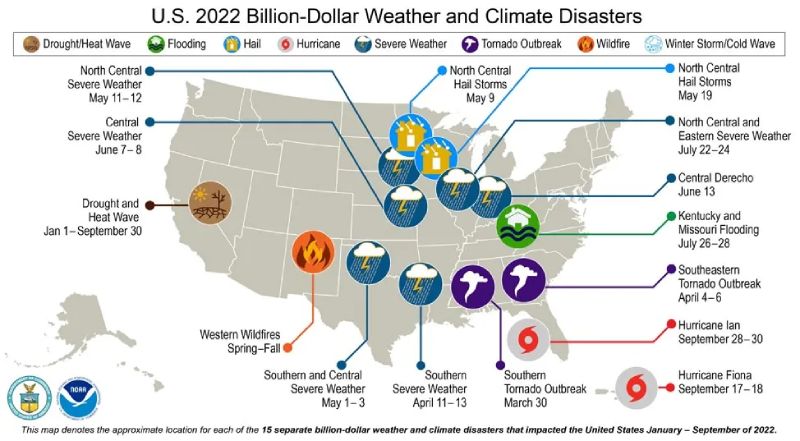

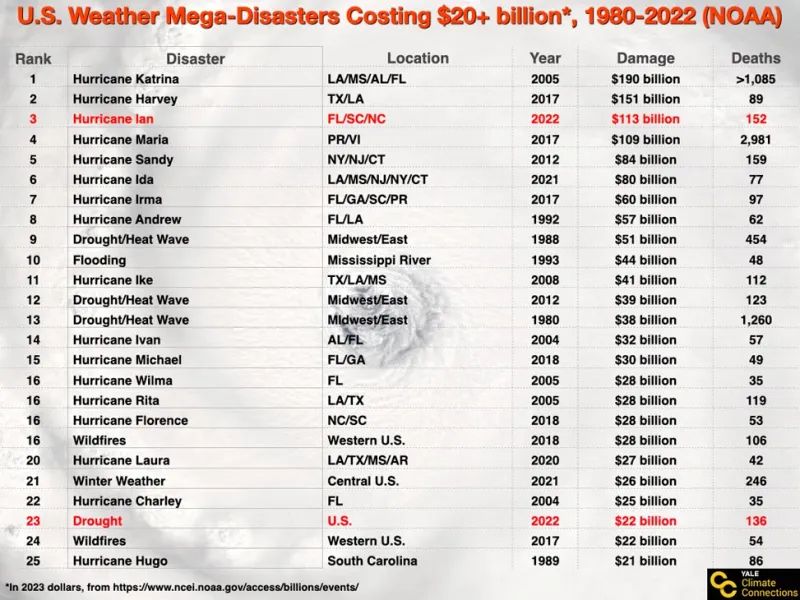

The contiguous United States suffered 18 billion-dollar weather disasters in 2022, according to NOAA, tied for the third-highest number in inflation-adjusted data going back to 1980. Only 2020, with 22 billion-dollar weather disasters, and 2021, with 20, had more. NOAA also reported that 2022 ranked as the 18th-warmest year since 1895.

The total cost of 2022’s billion-dollar weather disasters, $165 billion, was the third-highest on record, behind 2005 and 2017. Five of the last six years (2017-2022, with 2019 being the exception) have each had a price tag of at least $100 billion. Billion-dollar events account for 80-85% of the total U.S. losses for all weather-related disasters.

Billion-dollar weather disasters in the U.S. killed 474 people in 2022, compared to 688 in 2021. NOAA’s 2022 billion-dollar weather disaster list included 11 severe storm events, three hurricanes, one flood, one winter weather event, one drought, and one wildfire event.

NOAA’s 1980-2022 annual inflation-adjusted average is 7.9 billion-dollar events, but over the past five years (2018-2022), the annual average has more than doubled, to 17.8 events. NOAA reported that the number and cost of disasters are increasing over time as a result of:– Increased exposure (i.e., more people with more stuff );

– Increased vulnerability (i.e., more people living in flood plains, on barrier islands, etc.); and

– Climate change increasing the frequency of some types of extremes that lead to billion-dollar disasters.

Figure 1. The 18 billion-dollar U.S. weather disasters of 2022. (Image credit: NOAA)

Figure 2. Costliest U.S. weather disasters (2022 dollars) since 1980 from NOAA’s list of billion-dollar weather events.

Hurricane Ian the third-costliest weather disaster in world history

Heading up NOAA’s list of 2022’s billion-dollar weather disasters was Hurricane Ian, which powered ashore along the southwest Florida coast at Cayo Costa Island Sept. 28 as a category 4 storm with 150 mph winds and a central pressure of 940 mb, tying as the fifth-strongest hurricane on record (by wind speed) to make a contiguous U.S. landfall. NOAA estimated damage from Ian at $112.9 billion. Based on the EM-DAT international disaster database, this makes Ian the third-costliest weather disaster in world recorded history, behind only Hurricane Katrina of 2005 and Hurricane Harvey of 2017. The top eight most expensive weather disasters globally were the U.S. hurricanes at the top of the list in Figure 2.

As noted in our 2022 hurricane-season roundup, four named storms made a U.S landfall in 2022, with Hurricane Ian being the most destructive. The other landfalls were category 1 Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico (Sept. 17, $2.5 billion in damage), and category 1 Hurricane Nicole in Florida (Nov. 10, $1 billion in damage). Tropical Storm Colin’s landfall in South Carolina on June 5 did no appreciable damage.

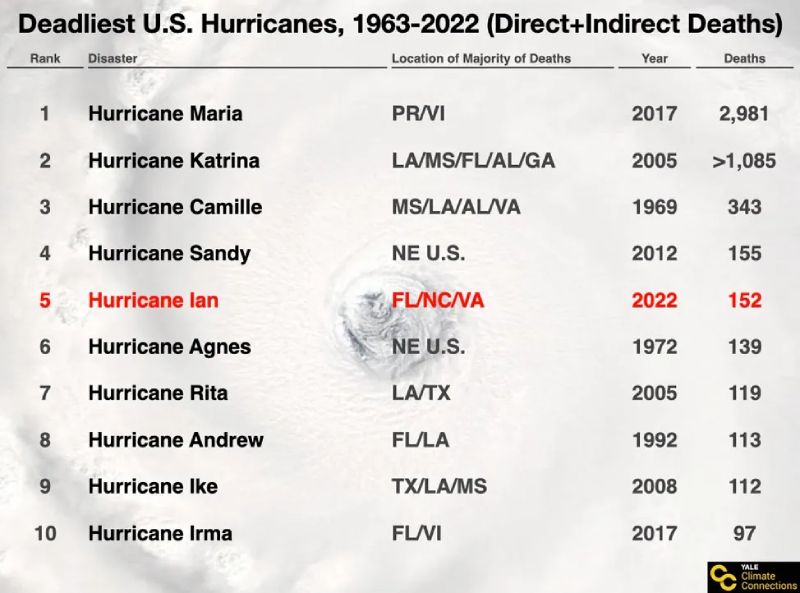

Figure 3. Deadliest U.S. hurricanes of the past 60 years for direct and indirect deaths. Data from 2016 – 2022 is from NOAA’s list of billion-dollar weather events; death tolls from 1963 – 2015 were taken from a 2016 paper, Fatalities in the United States Indirectly Associated With Tropical Cyclones. Indirect death tallies are unreliable prior to 1985.

Hurricane Ian the fifth-deadliest U.S. hurricane since 1963

The death toll from Hurricane Ian was unusually high for a U.S. hurricane in recent decades. NOAA’s put Ian’s direct and indirect death toll at 152, making Ian the fifth-deadliest U.S. hurricane in the past 60 years, according to statistics of maintained by key federal agencies (Figure 3). Causes of direct deaths include drowning in storm surge, storm-driven waves, rip currents, or freshwater flood from rain; falling trees are also a common source of direct deaths. Causes of indirect deaths include falls during post-storm clean up, traffic accidents, carbon monoxide poisoning from generators, and medical issues compounded by a hurricane.

Dozens of deaths from Ian have been attributed to drowning, both from storm surge and inland flooding. This runs counter to a recent trend in U.S. hurricanes toward indirect fatalities and away from direct fatalities (see our post from June 2022).

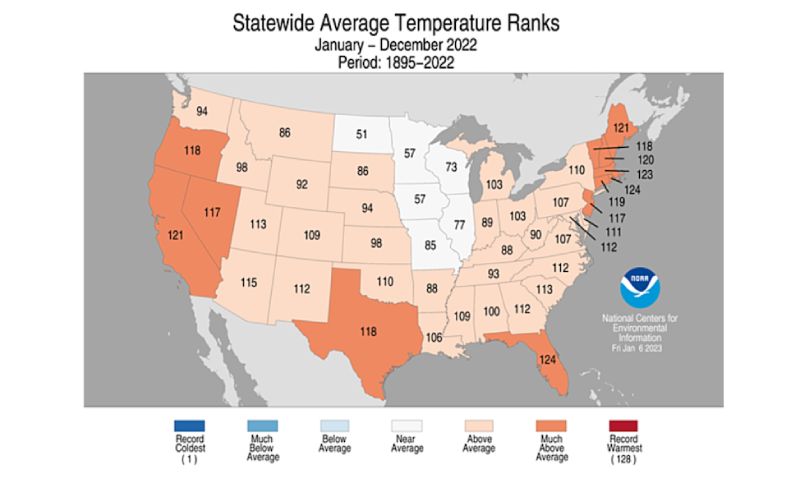

Another warm year in the U.S.

In its preliminary annual round-up of U.S. climate, also released on January 10, NOAA found that 2022 ranked as the 18th-warmest year since 1895. Florida, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, California, New Hampshire, Maine, and Connecticut had a top-10 warmest year on record; no states had temperatures considered below average. Every year since 1996 has been warmer across the Lower 48 than the 1901-2000 average, and the eight warmest years on record all have occurred in the 21st century (although 2022 was not in that group of eight).

Figure 4. Rankings of average temperature in 2022 for each contiguous U.S. state across records going back to 1895. Higher numbers (from 1 to 127) denote warmer values. (Image credit: NOAA/NCEI)

The contiguous U.S. has now warmed by around 2°F (1.1°C) since 1895, on par with the global average of 2°F (1.1°C) during the same period. That’s a noteworthy trend given that the U.S. was lagging much of the globe in long-term warming during the late 20th century.

Based on preliminary data from NOAA compiled by independent meteorologist Guy Walton, the U.S. in 2022 had 33,256 daily record maximums and 18,117 daily record minimums, a ratio of almost 2-to-1. A 2009 paper by Walton and colleagues predicted that the typical ratio could reach 20-to-1 by mid-century and 50-to-1 by late in the century.

The standout season in 2022 was summer, which was the third-hottest on record for the contiguous U.S., just 0.06°F below 2021 and 1936. This makes 2021 and 2022 by far the hottest pair of consecutive summers in U.S. records.

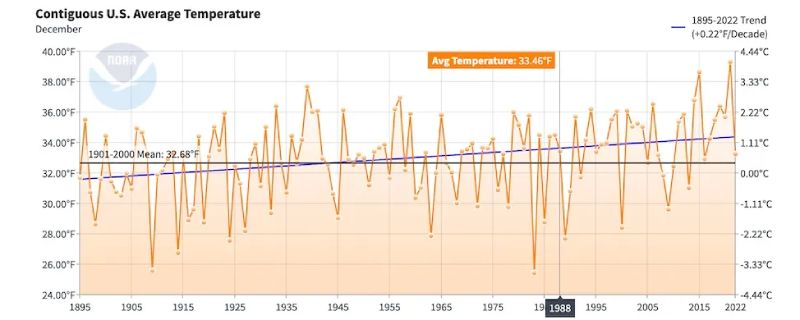

One of the banner weather events of the year was the spectacularly sharp cold wave that plowed across most of the northern, central, and eastern U.S. during the third week of December. The cold blast led to amazing temperature drops in many locations, including the largest on record at sites ranging from Denver to New York City. The latter was observed at Central Park, where New York records have been kept since 1869, making it an especially noteworthy event.

The worst single outcome from the Arctic blast was a horrific snowstorm in and near Buffalo, New York, that combined local lake-effect and larger-scale weather processes to produce white-out blizzard conditions for hours on end. Even in a city familiar with intense snow, the storm surprised people with its utter ferocity. At least 41 people were killed in the Buffalo area, including 17 people on foot who were found dead in snowbanks.

Although the nation’s brutal pre-holiday cold was not especially prolonged, it caused pipes to burst in countless buildings, leading to widespread water damage. Much milder weather preceded and followed the Arctic blast in most parts of the country, and the full-month national average came in very close to the typical temperature for December (65th coolest in the 128 years since 1895).

Figure 5. Average temperatures across the contiguous U.S. for each December since 1895. The long-term monthly average is now above 34°F, whereas it was below freezing in the early 20th century. (Image credit: NOAA/NCEI)

#NationalfireNews: As of December 31, 2022, the states with the most acres burned from wildfires are Alaska, New Mexico, Texas, Oregon and Idaho. More statistics will be published in the NICC annual report that should be available by February 1, 2023. pic.twitter.com/gi17jsEPeO

— National Interagency Fire Center (@NIFC_Fire) January 7, 2023

A big wildfire year in Alaska, but relatively quiet in California

Intense heat and drought led to another summer of destructive forest fires across the West, although the biggest impacts by far were in sparsely populated Alaska. According to the National Interagency Fire Center, the annual U.S. total acreage burned in 2022 – 7.53millionacres – was considerably less than the 10-million-plus acres consumed in 2020, 2017, and 2015, and the 8.7 million in 2018, but above the 4.6 million in 2019 and 7.1 million in 2021.

The U.S. acreage burned in wildfires in 2022 was far above average in Alaska but much closer to the recent average in the other 49 states combined. Of the 7.53 million U.S. acres burned in all 50 states in 2022, more than 3 million acres were in Alaska, with less than 5 million elsewhere. In contrast, during 2020 and 2021, Alaska saw far less than 1 million acres burned, while the other 49 states experienced close to 10 million and 7 million acres burned, respectively.

After a hellacious string of awful fire years in California (4,090,000 acres burning in 2020, and 2,230,000 acres in 2021, the highest and second-highest acreage in modern records), 2022 saw a much more manageable level of fire activity in the state: about 364,000 acres burned. In an interview with the LA Times, Park Williams, an associate professor of geography at UCLA, said, “We got really lucky. By the end of June, things were looking like the dice were loaded very strongly toward big fires because things were very dry, and there was a chance of big heat waves in the summer, and indeed we actually did have a really big heat wave this summer in September. But that coincided with some really well-timed and well-placed rainstorms.” A $2.8-billion investment in wildfire resilience projects over the last two years for forest management work, prescribed burns, and community outreach was also credited with contributing to the relatively quiet fire season. Unfortunately, the California fire season was deadlier than in 2022, with nine fatalities, all civilians, compared with three firefighter deaths in 2021.

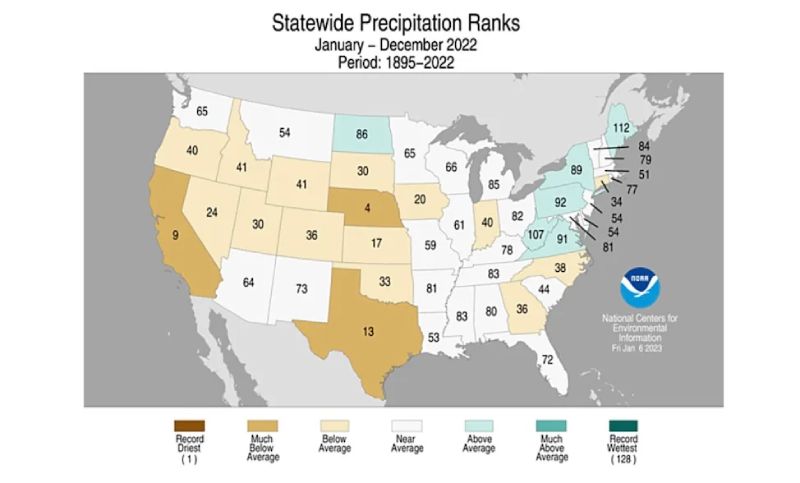

Figure 6. Rankings of average precipitation for each contiguous U.S. state in records going back to 1895. Darker green colors indicate wetter conditions; darker brown denotes drier conditions. (Image credit: NOAA/NCEI)

Fourth-costliest year for drought since 1980

Damages from devastating drought that gripped much of the nation in 2022 amounted to $22.2 billion, making it the fourth-costliest year for drought since 1980. Only 1988 ($51 billion), 2012 ($39 billion), and 1980 ($38 billion) had more expensive droughts (in inflation-adjusted dollars). At least 40% of the contiguous U.S. has been in drought for the last 119 weeks, setting a record in the 22-year U.S. Drought Monitor history. The previous record was 68 consecutive weeks (June 2012 – October 2013).

As is often the case, precipitation was a mixed bag for the United States when averaged by state and across the full year, although drier conditions predominated: Only six states were wetter than average, and none of those placed in the top 10. California and Nebraska had top-10-driest years on record, and most of the western U.S. was drier than average for the year. Clearly, the nation remains far from the widespread sogginess that was in place several years ago, when the nation’s wettest 12 months on record were recorded (37.93 inches from July 2018 to June 2019).

It’s possible we are turning a corner in 2023, as heavy rains and mountain snows have brought precipitation well above average across most of the West for the current water year that began in October. Moreover, the three-year La Niña event still in place is predicted to transition to neutral conditions by spring and perhaps to El Niño by late in the year.

Editor’s note: The post was corrected on January 11 for an error in the number of record daily high and low temperatures compiled by Guy Walton.