Image: Wikimedia Commons

Ojibway elder Basil Johnston said that a good life is impossible for people disconnected from their history. We must know who we are. The venerable historian William Cronon was the son of a history professor. One day, his father gave him the magic key for understanding the world. He told his son to carry one question on his journey through life: ‘How did things get to be this way?’

Sometime, when you’re feeling a bit bored, eager for thrills and excitement, get a library card and spend the next 20 years reading. Search for answers to Cronon’s question. Read 500 books on environmental history, ecology, anthropology, night after night, year after year, and type thousands of pages of notes.

It’s a mind-altering experience, a spiritual journey. In the process, you become something like a shaman, with the ability to pass through the veil, and discover important information in a non-ordinary state of consciousness. When you return to the ordinary reality, you can share what you have learned, and guide your people closer to the path of healing — in theory.

More commonly, finding real answers to Cronon’s question turns you into a notorious dolt, a filthy and disgusting pariah. Doomer! Go away! You’re crazy! Most folks prefer to remain in a world of illusions, a realm that has little in common with the power visions of the history shaman. Illusions are comfortable. The economy is recovering. We’re zooming toward Utopia. The best is yet to come. Right?

Conservation writer Charles Little has given many lectures on tree death in America. He is often asked one question: ‘A hand will be raised at the back of the room. “But what can we do?” the petitioner will ask. Do? What can we do? What a question that is when we scarcely understand what we have already done!’ Indeed! How can the human journey avoid one more cycle of repeated mistakes when we fail to understand most of the mistakes?

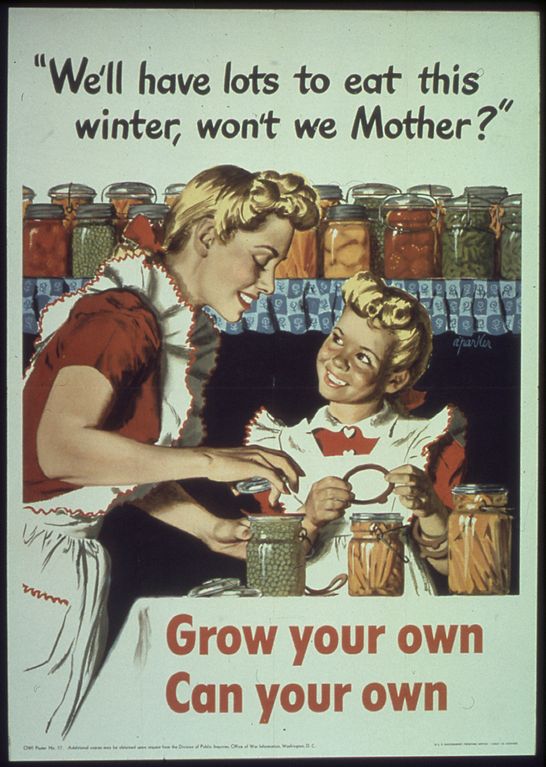

Biologist Paul Ehrlich once spent time among the Inuit of Hudson Bay, Canada. He was shocked to discover that the entire knowledge-base of their cultural information was known by everyone — how to hunt seals, tan pelts, weave a net, sew a coat, and so on. Yet, in our advanced civilisation, nobody knows even a millionth of our cultural information. You can get a PhD from Stanford and never learn anything about agriculture. Food is one thing we truly need. What is the plan for feeding 11 billion? Is it possible?

Meanwhile, mainstream society has invented a comical joyride in magical thinking — if we simply call something ‘sustainable’ enough times, then it is! In the blink of the eye, forest mining becomes Sustainable Forestry™ and soil mining becomes Sustainable Agriculture™. In a barrage of oxymorons, business as usual is kept on life support, by any means necessary, for as long as possible. What should we do about this? How can we revive the original meaning of sustainability?

In Against the Grain: How Agriculture has Hijacked Civilization, Richard Manning writes, ‘There is no such thing as sustainable agriculture. It does not exist.’ He says, ‘The domestication of wheat was humankind’s greatest mistake.’ In Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations, geologist David Montgomery concurs. ‘Continued for generations, till-based agriculture will strip soil right off the land as it did in ancient Europe and the Middle East. With current agricultural technology though, we can do it a lot faster.’ Contrary to common beliefs, history shamans have a hard time finding examples of genuinely sustainable agriculture. Have you seen recent images of Uruk, the magnificent city of King Gilgamesh?

In Here on Earth, Tim Flannery said that we are like sheep in a pasture. We no longer need big brains, because our shepherds take care of us. We have become ‘helpless, self-domesticated livestock.’ ‘While we sit in our air-conditioned homes and eat, drink and make merry like cattle in a feedlot without the slightest thought about the consequences of our consumption of water, food and energy, we only hasten the destruction — in the long term — of our kind.’ Won’t it be a healthy change when the lights go out, and we are once again required to be fully present in reality?

Flannery said that our ice age ancestors had bigger brains than we have now — 10 percent larger in men, and 14 percent in women. In Lone Survivors, Chris Stringer noted that the people of today have brains that average 1350 cc in size, and this is ten percent smaller than the average size of Homo sapiens brains 20,000 years ago. The average Neanderthal brain was 1600 cc — much bigger than ours. Could that imply something?

Anthropocentric scholars are fond of dismissing Neanderthals as dullards, because their tool kit changed little over 350,000 years. For 350,000 years, they lived by killing megafauna, but failed to wipe them out. Flannery noted, ‘Mammoths, straight-tusked woodland elephants, and two species of woodland rhinoceros coexisted with Neanderthals for hundreds of thousands of years.’ What was wrong with our incompetent cousins?

Today, every newborn that squirts out of the womb is a wild animal, with genes fine-tuned for life on a healthy tropical savannah. Infants only become consumers by being raised in consumer society. If we had been raised in a Neanderthal culture, would we live in balance?

In The Tender Carnivore, Paul Shepard wrote that when scientists raised chimps in their home, along with their own children, the chimps were at least as intelligent as children, until the children were three or four, learned language, and left the chimps in the dust. Different intelligence allows us to better comprehend the complexity of the world, but it also enables us to better destroy it. Much of our cultural information will be lost forever when climate change pulls the curtains on life as we know it. How can we preserve the tiny portion of this knowledge that is needed for a return to the path of good life?

Recently, I’ve become fascinated by our closest living relatives, the chimps and bonobos. We share something like 99 percent of our genes with them. Their ancestors have inhabited the same place for millions of years, without trashing it. Imagine that! They still enjoy a healthy life in a healthy place. Is that really so terrible? Once upon a time, our ancestors lived in the same region, in much the same way. What happened?

Chimps and bonobos did not make serious weapons, wage war against ape-eating predators, spread around the world, invent agriculture, explode in numbers, live in filth, and die by the millions from infectious diseases. They did not wage war against infectious diseases, soar into extreme overshoot, load the atmosphere with crud, and blindside the planet’s climate. Instead, they inhabit a niche in their ecosystem, and live as they have for millions of years, without rocking the boat. Is there something we could learn from their example?

Is it time to burn our Superman and Superwoman uniforms, apologise to the family of life for our furious rampages, return to the tropics, abandon words, clothes, and spears, and try to remember who we are? Can we recover a mode of enduring simplicity and stability that would no longer require a history to guide us? Can we someday heal so well that we never again have to ask ‘How did things get to be this way?’

—

Richard Reese lives in Eugene, Oregon. He is the author of What Is Sustainable, Sustainable or Bust, and Understanding Sustainability. His primary interest is ecological sustainability, and helping others learn about it. His blog wildancestors.blogspot.com includes free access to reviews of more than 150 sustainability-related books, plus a few dozen rants.