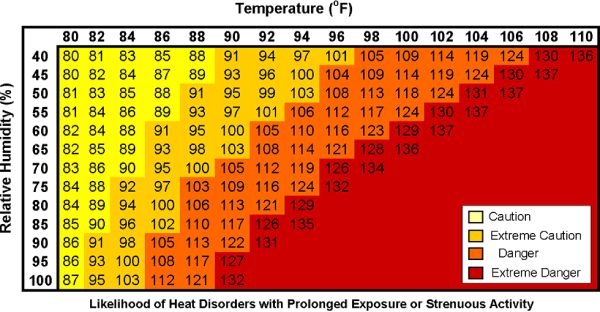

I’ve been questioned lately about wet-bulb temperatures and their impacts on plants and non-human animals. As I have reported frequently in this space, wet-bulb temperatures represent a combination of high temperature and high humidity. This combination leads to organ failure and therefore death in human animals.

So far, we have not reported on the impact of wet-bulb temperatures on plants and non-human animals. This short video attempts to overcome this oversight.

Yes, a few of us can live on the International Space Station—for a while. Yes, a few of us can live in Antarctica—for a while. In both cases, we depend upon technology created in comfortable laboratories here on Earth. We also depend heavily upon food created here on Earth. And, when I say here on Earth, I mean extensive grain-producing areas such as the Great Plains of North America and other relatively cool locations with predictable patterns of precipitation and temperature. Antarctica and the International Space Station do not fall into the category of production centers for high-yield agriculture. I don’t mean to be overly critical, but most people I know can barely make a sack lunch for themselves.

It’s not only everybody except me who has issues with living beyond the contemporary set of living arrangements. I suspect we’ve all had days in which disruptions in technology have left us frustrated and even angry. There was a time when I was younger and even more foolish when I tried to fix my toilet that was leaking a few milliliters of water every few days. After my feeble and frustrating attempt, I called upon a trained professional to fix the damn thing. And he did, for a few hours of labor and a few hundred dollars. Most of us have called upon trained professionals because we lack the ability or patience to fix what’s broken. Hope rarely fixes anything. After all, hope is defined by my online Merriam-Webster Dictionary as “to want something to happen or be true.” As you undoubtedly know, wishing thinking rarely fixes anything. Perhaps you are familiar with a line from the 2015 film, Mad Max: Fury Road. Spoken by Tom Hardy playing the part of Max Rockatansky, the line goes like this: “You know, hope is a mistake. If you can’t fix what’s broken, you’ll, uh … you’ll go insane.” Hoping my toilet would fix itself had the same impact as hoping somebody will create cooling centers that will allow us to remain comfortably alive.

Temperature affects the reproductive capacity of organisms and enzyme-linked chemical reactions in the cells. Temperature also affects growth, development, and morphology. As any rational person would expect, different species have different ranges of temperature tolerance. Evolution by natural selection ensures that every species in the environment they call home is perfectly matched to that specific environment. Even minor changes in the environment, such as small increases in local temperature or precipitation, negate the ability of that species to survive in that particular location. Similarly, the introduction of a novel species can and often has led to catastrophic outcomes for the species native to that location. Think, for example, of the American chestnut, Castanea dentata. A dominant tree in forests of the eastern United States, this tree towered above others until about the turn of the 20th century. At this time, the causal agent of chestnut blight, Cryphonectria parasitica, was inadvertently introduced from Europe, probably via the shipping of other materials. The remaining American chestnut trees are tiny sprouts from existing stumps. The species no longer supplies strong, rot-resistant timber. It no longer supplies edible nuts, either. Let’s call it yet another case in the category of mistakes have been made.

According to a peer-reviewed paper published in The Lancet Planetary Health titled, The upper temperature thresholds of life: “preferable and harmful temperatures are similar for humans, cattle, pigs, poultry, fish, and agricultural crops.” The paper in The Lancet Planetary Health was published on 10 June 2021, and it includes this information: “as global temperature increases with climate change, the effect on particular eukaryotic life forms will have direct and indirect consequences for society. High temperature will cause heat strain and affect the functioning and health of humans, the growth and productivity of livestock and poultry, and the growth and yield of crops. Organisms react to heat stress physiologically and by changing their behaviour. Physiological reactions include increased body temperature, increased heart and respiration rate, vasodilatation, increased sweating, and muscle cramps (an early symptom of heat illness). … Behavioural coping mechanisms for humans and animals include drinking more, eating less, limiting activity, and, for humans, dressing appropriately. Increased sweating can lead to water and salt loss that has to be compensated by increased water intake to avoid dehydration. … At very high temperature, exposure becomes lethal.”

There’s more, of course, from the peer-reviewed paper. “Climate change might cause population-level disturbances and cause ecosystem-level, or trophodynamic, effects in fish with direct implications in their distribution, abundance, and growth.” All of this information leads to the obvious conclusion that rapid environmental changes are bad for humans and non-human species.

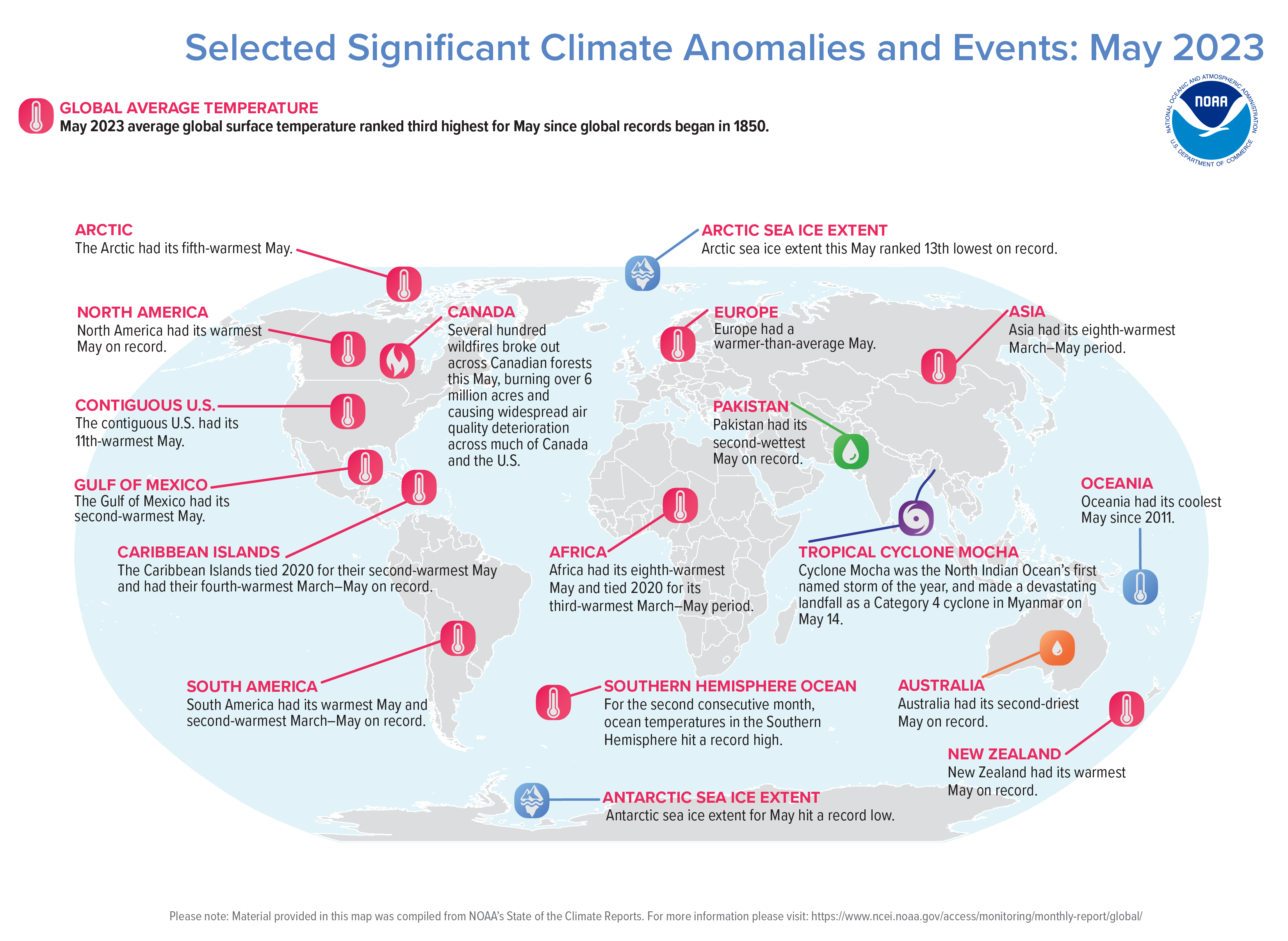

Additional information from the peer-reviewed paper suggests some likely future events, many of which are already underway. This is one of the problems associated with relying upon peer-reviewed literature: The conservative nature of the peer-reviewed process often results in predictions about the distant future that are already happening. Consider the following information, which I quote directly from the peer-reviewed paper: “heatwaves have been occurring frequently in major breadbasket regions due to specific patterns of the meandering midlatitude jet stream, with negative impacts on global food security.” Okay, so far, so good. But then, there’s this: “With a business-as-usual climate change scenarios of future greenhouse gas emissions, densely populated agricultural regions of south Asia—the basins of the Ganges and Indus rivers, where about a fifth of the global population lives—are expected to have frequent deadly heatwaves and wet bulb temperatures higher than 35°C by the end of the 21st century.” As we have reported in this space previously, these kinds of events are already occurring. The peer-reviewed paper catches up, slightly, with this information: “To place heatwaves into a more tangible perspective, Australia's increasingly frequent heatwaves are already taking a toll on people, crops, wildlife, and livestock species. For instance, in 2018, a 2-day heatwave, with temperatures above 42°C, killed a third of the population (23,000) of the bat species, Pteropus conspicillatus …, known as the spectacled flying fox. Continued global warming will gradually become lethal to other species if they cannot avoid, migrate, or otherwise protect themselves from extreme or extended temperature stress. Genetic adaptations to the current rate of climate change often need many generations, and the available time is too short for many complex forms of life. If the current trajectories towards a so-called hothouse earth continue, most creatures discussed in this [paper] Personal View, and many more, could be severely affected or could disappear completely.”

As we have reported several times in this space, quoting from the incredibly scientifically conservative political body known as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Earth is in the midst of the most rapid rate of environmental change in planetary history. According to the IPCC’s 8 October 2018 report Global Warming of 1.5o, “even abrupt geophysical events do not approach current rates of human-driven change.”

In addition, as we have reported previously in this space, even the IPCC has concluded that climate change is irreversible. This conclusion was reached by the IPPC in its 24 September 2019 report, IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. The conclusion of irreversibility was attributed to an overheated ocean. Remember, only one self-reinforcing feedback loop is required to ensure the irreversibility of climate change.

In other words, the IPCC has concluded that climate change is stunningly abrupt and also irreversible. As we have reported previously in this space, the IPCC was designed to fail when it was created during the Reagan administration. And yet, the IPCC has correctly concluded that climate change is occurring more rapidly than at any time in planetary history. Amazingly, humans are driving a faster rate of change than the meteor that hit the Yucatán peninsular about 66 million years ago, thereby driving dinosaurs to extinction.

So-called cooling centers will not save us. And who wants to walk out of one of these places only to encounter a planet devoid of life, except for humans? That’s not a cause for concern, by the way: Our species depends heavily upon other species for our own survival. To believe we’ll get along without an abundance of other lifeforms is pure hubris, the likes of which can only be found among individuals within the species Homo sapiens.