Originally published 24 Oct, 2021

Tensions between Russia and NATO are at an all-time high. But instead of seeking a way off the ladder of escalation, the US-led bloc’s new plan for hybrid war risks accelerating an already dangerous lethal arms race with Moscow.

There’s a concept in international relations, almost one of the first that students learn, called the ‘security dilemma’. It’s hardly rocket science, but it’s something governments and armed forces planners seem to consistently forget when it comes to making policy.

The idea is basically this: Country A feels threatened by country B; it therefore takes some measures – such as increasing its defence spending – to make itself more secure; but when country B sees what country A is doing, it in turn feels threatened, and so takes reciprocal measures of its own. The result is that country A ends up less safe than it was to start with.

The dilemma is that if you do nothing to strengthen your defences, you’ll be insecure, but if you do something you’ll end up worse off because of the counter-measures the other side will take. What do you do? If countries A and B both take action to defend themselves, they will find themselves in an ever-escalating process – what theorists like to call the ‘spiral model’, but which in public parlance is often called an arms race.

The obvious way out is to break the spiral. Avoid escalating and resort to other measures, such as negotiation and arms control. All it may take is for one side to unilaterally step back, and the vicious circle will turn into a virtuous one.

It’s pretty basic stuff, but again and again, state leaders choose to ignore it and prefer instead to march down the path of the spiral. So it is today in the case of Russian-NATO relations, which are as classic an example of the security dilemma as you could possibly hope to find. Deep down, there’s no fundamental reason for conflict, but mutual suspicion leads to a continuing ramping up of reciprocal measures that deepen the suspicion, leading to more measures, more suspicion, and so on, seemingly ad infinitum.

For instance, earlier this year, the Russian military undertook a series of exercises close to its Western borders. From a Russian perspective, these were purely defensive. From a Western perspective, they appeared potentially threatening, justifying in turn Western exercises that NATO claims are entirely for defence, but which Russia considers a threat, prompting further Russian measures.

The latest round in this dangerous process is the announcement this week that NATO has developed a new ‘masterplan’ to defend against a possible Russian attack. The plan itself is secret, so we don’t know its contents, but it’s said to focus on non-conventional war, including nuclear strikes, cyberwarfare, and even war in space. Geographically, it covers the whole spread of NATO’s border with Russia, from the Baltic to the Black Seas inclusive.

In part, this is just what military institutions do: They plan for possible future conflicts. The Russian military almost certainly also has similar contingency planning in place for a potential war with NATO. It would be very odd if it didn’t. In this sense, NATO’s new masterplan shouldn’t in theory be seen as a cause for alarm. Moreover, NATO insists that its purpose is not aggressive. Rather, the plan’s aim is deterrence, thus its formal title: ‘Concept for Deterrence and Defence in the Euro-Atlantic Area’.

However, as students of the spiral model know, reality is much less important than perception. Deterrence is a matter of signals. One sends a message to potential enemies that if they attack, they will suffer devastating consequences. The problem is that although this message may be clear to the one doing the signalling, it may not be so clear to the one to whom it is sent. You think you are deterring, but they think you are threatening. They therefore respond in kind. In this way, deterrence ends up being counter-productive.

This doesn’t always happen, but in this instance, it seems to be the case. Some aspects of NATO’s announcement seem unnecessarily escalatory, in particular the references to nuclear war. We’ve come a long way from the musings of nuclear strategists like Herman Kahn and Bernard Brodie, who tried to calculate how it was possible to fight and win a nuclear war. One shouldn’t be surprised that when other people hear such talk being revived, they’re not deterred but alarmed.

Unsurprisingly, Russia’s reaction to NATO’s new military concept has been decidedly negative. “There is no need for dialogue under these conditions,” Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said, continuing: “this alliance was not created for peace, it was conceived, designed and created for confrontation.”

From the Russian point of view, NATO’s actions justify Russia’s recent decision to sever ties with the Atlantic alliance. Rather than bringing Russia to heel, NATO may merely be driving it into an ever more hostile position.

In this way, the West’s perception of Russia as a threat becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The same, of course, could be said the other way around. For if the West perceives Russia as threatening, it is because of things that Russia has done – as it sees it, for its own defence. For instance, NATO argues that what has made its new plan necessary is Russia’s strengthening of its armed forces and its recent advances in military technology.

The more Russia defends itself, the more it incites NATO. And the more NATO defends itself, the more it incites Russia. A security dilemma par excellence. The risk both parties run is that the situation will continue to spiral further and further into ever more dangerous territory. Already this spring, Europe passed through a period of high tension in which it looked entirely possible (although unlikely) that war might erupt between Ukraine and Russia. Anything that contributes to a further worsening of the situation is therefore thoroughly undesirable. NATO’s new military plan, it seems fair to say, runs the risk of doing just that.

Author

Paul Robinson, a professor at the University of Ottawa. He writes about Russian and Soviet history, military history and military ethics, and is the author of the Irrussianality blog.

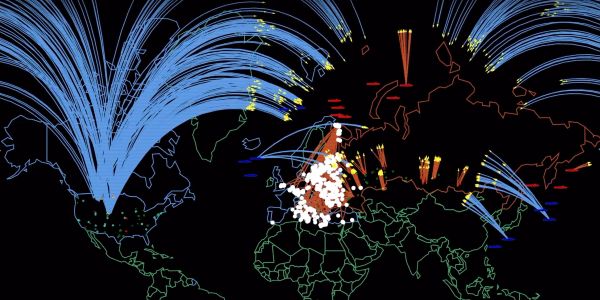

PLAN A - Princeton Science and Global Security

Our team developed a simulation for a plausible escalating war between the United States and Russia using realistic nuclear force postures, targets and fatality estimates. It is estimated that there would be more than 90 million people dead and injured within the first few hours of the conflict.

{vembed Y=2jy3JU-ORpo}

For more, see https://sgs.princeton.edu/the-lab/plan-a

A collaboration with Alex Wellerstein (http://blog.nuclearsecrecy.com) and Jeff Snyder (https://music.princeton.edu/people/je....

Nuclear War Simulation - NATO vs Russia

This realistic, facts-based simulation is divided into 3 stages: Nuclear War, Nuclear Fallout and Nuclear Winter. Watch this video to find out what will happen to the world during each of those stages.

{vembed Y=dxJHecyYBno}

Producer: Cristian Ibarra Santillán

Learn More:

What would happen if an 800-kiloton nuclear warhead detonated above midtown Manhattan?

Turning a Blind Eye Towards Armageddon

Nuclear War Map: what would happen in a nuclear war?

![]() Please help keep us afloat. Donate here

Please help keep us afloat. Donate here