The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-19 has largely faded from the public memory. It got its name from the Russians, who called it the Spanish Lady. In Spain, folks preferred to call it the French flu. Many thought it was a German bioweapon, despite the fact that the flu pounded the poor Germans so hard that they finally hurled Kaiser Wilhelm overboard, and eagerly signed an unconditional surrender, which brought an end to the insanity of World War One (1914-1918).

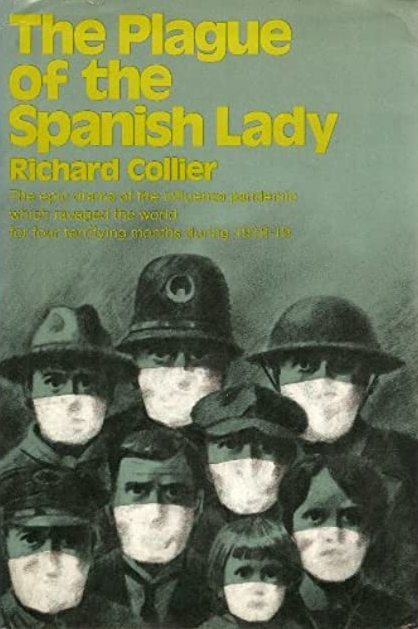

Richard Collier wrote a book about the pandemic, The Plague of the Spanish Lady. He was a journalist, and he described how the events unfolded in many localities. The virus appeared on the radar in March 1918, and was fading out by May of 1919. Collier focused his attention on the 17 week period when the flu had reached its maximum scale and mortality, beginning in early September 1918. The pandemic killed at least 20 million in just five months (others say 50 to 100 million). World War One, on the other hand, took five long and bloody years to rub out a mere 10 million lives.

For folks disgusted with the creepiness of life in the twenty-first century, Collier’s book provides a refreshing diversion. You will be so happy that you are not living in 1918! The only lucky group during that pandemic were the untouchables of India. The flu hit India the hardest, killing more than 12 million. Rivers were clogged with corpses. There were times when 700 people died every hour in Mumbai (Bombay). Since there was a social obligation to stay away from untouchables, far fewer of them got sick.

It was common for the flu to hit like a hammer. Folks might have some aches and pains for a few days, and then maybe a sore throat, and then maybe some large blisters on their face, back, or chest. High fevers were common. Folks coughed up blood, and many bled from their ears, nose, and/or eyes. Lungs filled with blood, and people turned blue from lack of oxygen — it was hard to tell white folks from blacks. Some called it the Purple Death. People wondered if the end of the world had arrived.

In late September 1918, a tram was carrying passengers through Capetown, South Africa. One passenger dropped dead, and was laid on the sidewalk for city workers. As the tram continued, four more riders died and were put off. Then the driver of the tram dropped dead.

In early October, an official of the Canadian Pacific Railroad, who was normally a good boy, violated the quarantine, filled a train with soldiers, intending to take them from Quebec City to Vancouver. At numerous stops, he left behind carloads of sick soldiers, unleashing the epidemic in each city. Arriving in Vancouver with the remaining survivors, he immediately jumped on an eastbound train, with plans to take another load of soldiers west. He learned about the deadly consequences of his foolish mission, and he had no remorse.

The Spanish flu had unusual effects. Flu bugs generally prey on kiddies or the elderly, but this one hit folks who had the strongest immune systems. Half of its victims were aged 20 to 40. My grandmother’s sister, Emma Amundson, died of the flu at 33, on November 19, 1918. She was a nurse who lived in a tiny village in middle of nowhere North Dakota. The railroad that ran through the village probably delivered a sample of the hellish disease from the outer world.

In 1918, there was no commercial air travel. To take a trip around the world took a year, via steam ship. The H1N1 flu virus zoomed around Earth in just two months. It moved by train, boat, bus, and camel caravan. In 2005, the virus was identified as being avian, birds carried it. Six miles off the coast of Tasmania, there was an island. In October, the husband and wife who ran the lighthouse had seen no visitors in three months. Birds brought the couple a yucky surprise. The flu also found isolated native settlements in Alaska, where starving sled dogs broke into cabins and ate the dead and dying.

In 2018, the hundredth anniversary of the Spanish flu, the BBC produced a fascinating report: The places that escaped the Spanish Flu. One advantage was living in a location that was isolated from the rest of the world. Another was super strict, zero-exception quarantines. Some communities were kept healthy by armed vigilantes who allowed no one to enter or leave. Of course, in 1918, folks in nonurban regions primarily dined on food conveniently produced close to home.

Today, the food story is very different. Dinner ingredients are often shipped in from around the world via complex energy-guzzling distribution systems. Another frightening difference is personal mobility. Many do not hesitate to board a plane and fly to faraway places, unintentionally transporting pests and pathogens. In 2018, airline passengers took a billion flights, domestic and international, to and from the U.S. Even more people routinely jump into their motorized wheelchairs and drive other cities or regions. Imagine how our super-mobility could turbocharge a highly virulent virus today. Yikes!

In 1918, Australia got a gold star for displaying above average intelligence, which led to below average infection rates. Eighty ships having infected people aboard were not allowed to dock. Smart! On land, 10,000 infected people were kept isolated from society. Brilliant!

Unlike many traditional epidemics that were empowered by lousy sanitation and hygiene, the rich, famous, and powerful got no mercy from the Spanish Flu. Mortality in plush neighborhoods was the same as in the slums. The Purple Death was an equal opportunity killer. In efforts to stop the spread, many cities closed schools, theaters, churches, saloons, race tracks, libraries, and all public meetings. Phone booths were boarded up. Caskets, in short supply, were rented. Folks were urged to walk, and stay off the street cars. In San Francisco, some courts were held outdoors in parks.

Communities that downplayed the risk of disease, and attempted to continue business as usual, often paid dearly for their mistake. In Kansas City, the Health Board tried to close saloons and theaters, but the mayor kept them open. More than 1,800 died. In Jamaica, the decision to not quarantine the sick led to 7,000 deaths.

On September 21, the SS Niagara departed from Vancouver, Canada, heading for Auckland, New Zealand. On October 9, when it landed in Fiji, 83 of those aboard had succumbed. Passengers were allowed to go ashore. Consequently, more than 8,000 died on Fiji’s 100 islands. Then, on October 11, the captain of the Niagara sent a message to New Zealand, notifying them that sickness was spreading on his ship. On October 12, the Niagara docked in Auckland — it was a floating hotbed of infection. The ship should have been quarantined, but wasn’t. Consequently, 6,680 New Zealanders died. On October 30, Auckland authorities allowed the SS Talune, with infected passengers, to depart for Samoa. “It was as if a death ray had struck the island” — 7,000 perished.

Another quirk of the flu was “apparent death,” in which the victim was cold, not breathing, and had no pulse. It was a deep coma. Quite a few were shaken out of comas inside their coffins. Hundreds each week may have been buried alive. In Cape Town, a notorious drunkard and wife beater, who had no friends whatsoever, screamed from his coffin on the way to the graveyard. The drivers of the wagon ignored him. “I reckon ain’t no one going to miss him.”

The grand finale of the Spanish flu was the glorious conclusion of “the war to end all wars” which occurred on November 11. The world erupted with immense celebration. Church bells pealed. Big Ben rang in London, ending four years of silence. All rules against public gatherings were disregarded, as the happy crowds hugged, kissed, and danced. Victory “ushered in the greatest medical holocaust in history.” In Cockermouth, England, which had entirely escaped the flu, one church service infected the whole town. The state of Louisiana reported 350,000 cases in the week after the celebration. Within a week, 19,000 died in Britain, and 17,000 doughboys died in France.

Collier’s book was published in 1974. In 2006, Dr. Michael Greger published Bird Flu, which focused more on medical analysis, rather than lively journalism. He estimated that the 1918 pandemic caused 100 million deaths. Almost all of humankind was exposed to the virus, and half of them experienced some level of infection, from mild to fatal. In the end, the flu ran out of victims. Essentially, you were either immune or dead.

Greger also presented uncomfortable information on how we’re getting even better at unintentionally encouraging flu viruses to mutate in new forms. The H5N1 virus that hit Hong Kong in 1997 was far more deadly than the H1N1 variant of 1918. Viruses keep themselves amused by constantly rearranging their proteins, so scientists who develop vaccines will never be out of work. The H1N1 virus is still around, in multiple new variants.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic rumbled onto the stage. It’s caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, not the influenza A H1N1 virus, but both types of virus are highly prone to “rapid viral evolution.” Mutations limit the long term effectiveness of vaccines. Many suspect that COVID-19 originated in the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan China, where many species of live animals are concentrated in impressively unsanitary conditions, creating a delightful playground for viruses of every size, shape, and color.

Collier, Richard, The Plague of the Spanish Lady, Atheneum, New York, 1974.

NB: The views expressed in this article regarding the origin of COVID-19 are those of the author and not of Titanic Lifeboat Academy or the editors of this website.

To-date there is no definitive data supporting the bat-Wuhan-market theory as the origin of COVID-19. The origin of the virus remains the subject of research and speculation, except on the MSM where every connection to China is propagandistically employed, e.g. "Wuhan virus", "SARS-2".

Several research papers into the virus' origin have been published in pre-print as this question continues to unfold. Pre-Print appear to be used in this case to get information out to other researchers as quickly as possible in order to speed the research process through sharing. Peer-reviewed publication, as most of you know, can take a year or more. To date, four separate papers (India, China, China2, France) showed the presence of unexpected ebola and HIV genes in the virus and a "furin-like cleavage site in the Spike protein of the 2019-nCoV, lacking in the other SARS-like CoVs". Some of these were "withdrawn" but the HIV/ebola genes presence has become established, though how ebola or HIV merged with the COVID-19 virus has not.

Without question China has the most COVID-19 data, the longest research on its outbreak, and a proven record of sharing both, e.g. here, here and here. JAMA has also published a number of these pre-print research papers from China.

We highly recommend that those who write for, read, and support non-MSM media turn to that same media (for the very same reasons they write for and support it) when searching for accurate information on COVID-19 or any other subject. ~ Ed.

Author

Richard Reese lives in Eugene, Oregon. He is the author of What Is Sustainable, Sustainable or Bust, and Understanding Sustainability. His primary interest is ecological sustainability, and helping others learn about it. His blog wildancestors.blogspot.com includes free access to reviews of more than 160 sustainability-related books, plus a few dozen rants. The blog is searchable by author, title, or topic.

Richard Reese lives in Eugene, Oregon. He is the author of What Is Sustainable, Sustainable or Bust, and Understanding Sustainability. His primary interest is ecological sustainability, and helping others learn about it. His blog wildancestors.blogspot.com includes free access to reviews of more than 160 sustainability-related books, plus a few dozen rants. The blog is searchable by author, title, or topic.