Part 1: Look a Gift Horse in the Mouth

As the digital revolution was underway in the mid-nineties, research departments at the CIA and NSA were developing programs to predict the usefulness of the world wide web as a tool for capturing what they dubbed “birds of a feather” formations.

That’s when flocks of sparrows make sudden movements together in rhythmical patterns.

They were particularly interested in how these principles would influence the way that people would eventually move together on the burgeoning internet: Would groups and communities move together in the same way as ‘birds of a feather’, so that they could be tracked in an organised way? And if their movements could be indexed and recorded, could they be identified later by their digital fingerprints?

To answer these questions, the CIA and NSA established a series of initiatives called Massive Digital Data Systems (MDDS) to directly fund tech entrepreneurs through an inter-university disbursement program, naming their first unclassified briefing for computer scientists ‘birds of a feather,’ which took place in San Jose in the spring of 1995.

Amongst the first grants provided by the MDDS program to capture the ‘birds of a feather’ theory towards building a massive digital library and indexing system – using the internet as its backbone – were dispersed to two Stanford University PHD’s, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, who were making significant headways in the development of web-page ranking technology that would track user movements online.

Those disbursements, together with $4.5 million in grants from a multi-agency consortium including NASA and DARPA, became the seed funding that was used to establish Google

Eventually MDDS was integrated into DARPA’s global eavesdropping and data-mining activities that would attempt total information awareness over US citizens. Few understand the extent to which Silicon Valley is the alter-ego of Pentagon-land, even fewer realise the impact this has had on the social sphere. But the story does not begin with Google, nor the military origins of the internet, it goes back much further in time, to the dawn of counterinsurgency and PSYOPs during the second world war.

The Dawn of PSYOPs

According to historian Joy Rhodes, a renowned physicist told U.S. defence secretary Robert McNamara in 1961: “While World War I might have been considered the chemists’ war, and World War II was considered the physicists’ war, World War III . . . might well have to be considered the social scientists’ war.”

The intersection of social science and military intelligence is recognised by the US Army to have begun during WWI when pre-war journalist Captain Blankenhorn established the Psychological Subsection in the War Department to coordinate combat propaganda.

These grey-area operations, as they become known, plateaued during World War II, when military strategists, building on wartime research in crowd psychology, drafted social scientists into the war effort through the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD). The office would aggregate information about the German people and develop propaganda and psychological operations (PSYOPS) to lower their morale. This culminated in 1942, with the US federal government becoming the leading employer of psychologists in the US.

OSRD was an early administration of the Manhattan Project and responsible for important wartime developments in technology, including radar. The agency was directed by engineer and inventor Vannevar Bush – a key player in the history of computing, known for his work on The Memex, an early hypothetical computer device, that would store and index a user’s books, records and other information, and which would go on to inspire most major advancements in the development of personal computers over the next 70 years.

As the second world war ended and a new threat emerged from post-war ravaged Europe, scholars and soldiers once again reunited to defeat an invisible and aggressively expansionist adversary.

Across the Soviet satellites in Europe and in the nations threatened by communism in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, cold war special operations, as they become known, were a nebulous category of military activity that included psychological and political warfare, guerrilla operations and counterinsurgency. To mobilise these ‘special warfare tactics’ the army established the Office of the Chief of Psychological Warfare (OCPW) in 1951, whose mission was to recruit, organise, equip, train, and provide doctrinal support to Psywarriors.

The office was directed by General Robert McClure, a founding father of psychological warfare and friend of the Shah of Iran, who was instrumental in the overthrow of Mohammad Mosaddegh in the 1953 Iranian coup d’état.

Integral to the projects of McClure’s OCPW, was a quasi-academic institution with a long history of military service called the Human Relations Area Files (HRAF). Founded by anthropologist turned FBI whistle-blower George Murdock, HRAF was set up to collect and standardise data on primitive cultures around the world.

During WWII its researchers worked hand in glove with naval intelligence to develop propaganda materials that would help the US liberate pacific nations from Japanese control. By 1954, the department had grown into an inter-university consortium of 16 academic institutions, funded by the army, CIA, and private philanthropies.

In 1954 the OCPW negotiated a contract with the HRAF to author a series of special warfare handbooks, disguised as scholarship, that sought to understand the intellectual and emotional character of strategically important people, particularly their thoughts, motivations and actions, with entire chapters compiled on the attitudes and subversive potentials of foreign nationals, while other chapters focused on the means of transmitting propaganda in each target nation, whether news, radio or word of mouth. This was, of course, decades before the internet.

SORO

In 1956, the Special Operations Research Office (SORO) emerged from these programs. Charged with managing the US Army’s psychological and unconventional warfare tactics during the cold war and taking the work of HRAF to the next level, SORO set about the monumental task of defining the political and social causes of Communist revolution, the laws governing social change and the theories of communication and persuasion that could be used to transform public perception.

SORO formed a central component of the Pentagon’s militarisation of social research, and particularly the ideas and doctrine that would usher in a gradual shift towards an American-led world order. Its research team was located on the campus of American University in Washington, D.C, and comprised the era’s pre-eminent intellectuals and academics.

SORO’s ensemble team, from the fields of psychology, sociology and anthropology, would immerse themselves in social system theory, analysing the society and culture of numerous target countries, particularly in Latin America, while confronting the universal laws governing social behaviour and the mechanisms of communication and persuasion in each jurisdiction. If the US Army could understand the psychological factors that sparked revolution, they could, in theory, predict and intercept revolutions before they got off the ground.

SORO was part of a rapidly expanding nexus of Federally Funded Research Centers (FCRC’s), that reoriented academia towards national security interests. Working at the intersection of science and the state, SORON’s, as they were known, advocated for an expert-directed democracy, regardless of the totalitarian consequences of social engineers and technocrats acquiring control over the thoughts, actions, and values of ordinary people.

In those early days of the cold war, academics and scientists working at the intersection of military and academia firmly believed that intellectuals should guide geopolitics. This was accepted as the most stable form of governance to take the free world into the next century. It explains how we have arrived under the rubric of the ‘settled science’ today. Or at least, policies masquerading as science. From the biosecurity state to the fundamentalism of climate science, much of what was achieved in those golden years of militarised social research shapes the twenty-first century.

By 1962, sixty-six federally funded military research institutions were in operation. Between 1951 and 1967, the number tripled, while funding skyrocketed from $122 million to $1.6 billion.

But as opposition to the Vietnam War intensified in the 1960s, a growing number of intellectuals, policymakers and academics became concerned that the national security state was morphing into the statist, globalist force it had been fighting during the cold war and began publicly criticising Pentagon-funded social scientists as technocratic social engineers.

This inspired a wave of discontent against the militarisation of social research to grip America, culminating in 1969 with the American University’s administrators banishing SORO from their campus and severing ties with their military partners. The move was endemic of the changing attitude towards these grey area special operations and resulted in the 1960’s and 1970’s with the excommunication of military research centres from university campuses across the US: a move that forced the military to look elsewhere – towards the private sector for their alternative warfare capabilities.

Following a long tradition of public-private military cooperation, from the Rand Corporation to the Smithsonian Group, these quasi-private institutions were being spun-out of the military at a rate of knots since the 1940’s.

Project Camelot

One of the programs conceived by SORO was ‘Methods for Predicting and Influencing Social Change and Internal War Potential’. Codenamed Project Camelot, the landmark program sought to understand the causes of social revolution and identify actions, within the realm of behavioural science, that could be taken to suppress insurrection.

The goal, according to defence analyst, Joy Rhodes, was ‘to build a radar system for left wing revolutionaries.’ A sort of ‘computerised early warning system that could predict and prevent political movements before they ever got off the ground.’

‘This computer system’ writes Joy Rhodes, ‘could check up to date intelligence against a list of preconditions, and revolutions could be stopped before the instigators even knew they were headed down the path of revolution.’

The research collected by Project Camelot would produce predictive models of the revolutionary process and profile what social scientists deemed ‘revolutionary tendencies and traits.’ It was anticipated that such knowledge would not only help military leaders anticipate the trajectory of social change, but would also enable them to design effective interventions that could, in theory, channel or suppress change in ways that were favourable to U.S. foreign policy interests.

It was intended that the information gathered by Project Camelot would funnel into a large ‘computerised database’ for forecasting, social engineering, and counterinsurgency, that could be tapped at any time by the military and intelligence community.

But the project was beleaguered by controversy when academics in South America discovered its military funding and imperialist motives.

The ensuing backlash resulted in Project Camelot being, ostensibly, shut down, though the core of its project survived. Multiple military research projects picked up on Project Camelot’s ‘early warning radar system for left wing revolutionaries,’ while its computerised database for ‘forecasting, social engineering, and counterinsurgency’ went on to inspire a nascent technology developed in the years to come, that would eventually become known to the world as the internet.

The Military Origins of the Internet

As Sasha Levine reveals in his ground-breaking book, Surveillance Valley, at the height of theCold War, US military commanders were pursuing a decentralised computer communications system without a base of operations or headquarters, that could withstand a Soviet strike, without blacking-out or destroying the entire network.

The project was coordinated by the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), created by President Eisenhower in 1958, for the development of technologies that would expand the frontiers of science and technology and help the US close the missile gap with the Soviets.

DARPA has been at the vanguard of every major advancement in the development of personal computers since the cold war, culminating in 1969 with the first computers arriving in universities across the US.

A few years later DARPA would develop the protocols to enable connected computers to communicate transparently across multiple networks. Known as The Internetting Project, DARPA’s prototypical communications network, the ARPANET, was born in 1973.

The project was eventually transferred to the Defence Communications Agency and integrated into the numerous new networks that had emerged. By 1983 the ARPANET was divided into two constituents: MILNET to be used by military and defence agencies, while the civilian version would retain the ARPANET handle.

Fast forward to 1990 and the ARPANET was officially decommissioned, and the Internet privatised to a consortium of corporations including IBM and MCI. Eventually the federal government created a dozen or so network providers and span them off to the private sector, building companies that would become the backbone of today’s internet, including Verizon Time-Warner, AT&T and Comcast.

That’s the same handful of corporations who not only own 90% of US media outlets, but also control the flow of global communications, through a process of absolute vertical-horizontal alignment of legacy media with digital media, and the infrastructures and technologies that enable their mass communication, including cable, satellite and wireless, the devices and hardware, software and operating systems.

J.C.R. Licklider

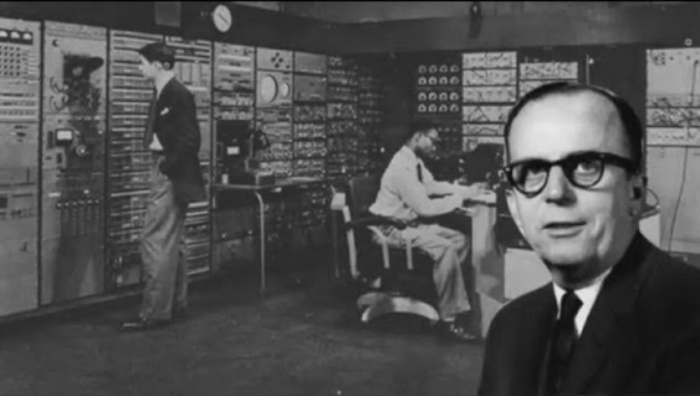

A central player in the development of the ARPANET, who many consider the founding father of computing, was American psychologist, J. C. R. Licklider.

Lick, as he was known, was the first director of the agency tasked with executing DARPA’s information technology programs, The Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO), that has been responsible for just about major advancement in computer communications since the sixties.

As Stephen J. Lukasik, a contributor to the ARPANET project reflected in his paper ‘ ‘Why the Arpanet Was Built’, ‘Lick saw information technology and behavioural and cognitive science issues as connected.’

Lick was essentially predicting how the internet would go on to evoke real world social processes that would radically transform how we communicate, organise and process information. It is no coincidence that a psychologist of Lick’s calibre was at the vanguard of a new technology designed to exploit basic vulnerabilities in the human psyche.

In the 1960’s Lick oversaw DARPA’s strategic interest in a new frontier of information technology, called Brain Computer Interfaces (BCI’s). In his famous paper, considered one of the most important in the history of computing, Lick put forward the then radical idea that the human mind would one day merge seamlessly with computers.

He was anticipating the evolution of AI and the role that DARPA would go on to play in funding just about every major advancement in BCI technology over eight decades, including Elon Musk’s fully-implanted, wireless, brain-machine Ninterface company, Neuralink.

The Vietnam War

The ARPANET brought together the Pentagon’s war machine with university research departments and the Bay area’s counterculture scene, inspiring much of the anecdotal idealism that would define the early years of cyberspace as a liberating new frontier for humanity.

Cyberspace, it was claimed by its early adopters, would free information and provide universal connectivity. The realms of possibility were, indeed, endless.

But war hawks and intelligence analysts had other ideas. If the lessons of the Vietnam war were anything to go by, the future of US warfare would not be with nation states, it would be with ideologies, or more specifically, grassroots movements, such as the Viet Cong, who had the power to stoke the flames of civil unrest, that could lead to uprisings, or worse, revolution. Alternative approaches were, therefore, needed to infiltrate and disrupt this new threat to the ‘free world’.

As the war raged in Southeast Asia, another psychology PhD, Robert Taylor, joined DARPA as the agency’s third director. Taylor transferred to Vietnam in 1967, to establish the first computer centre at the Military Assistance Command base in Saigon, a central pillar in the DoD’s psychological warfare operations. The move was symptomatic of the changing rules of military engagement that saw DARPA, and indeed, this new technology, playing a major role in the war effort, both in Southeast Asia, and at home on US soil, against the growing anti-war movement.

In 1968, Taylor and ‘Lick published their seminal paper ‘The Computer as a Communication Device’, laying out the future of what the Internet would eventually become. The paper began with the visionary statement: “In a few years, men will be able to communicate more effectively through a machine than face to face,” anticipating the meteoric rise of social media, particularly Facebook, in the decades to come.

Bringing the PSYOP back home

The origins of Facebook coincide with a controversial military program that was mysteriously shut down the same year Facebook launched.

The military program in question, LifeLog, was developed by DARPA’s Information Processing Techniques Office, with the stated aim of creating a permanent and searchable electronic diary of a person’s entire life – a dataset of their most personal information, including their movements, conversations, connections, and everything they listened to, watched, read and bought.

But would people willingly give up a record of their private lives to a military intelligence social media platform?

Probably not. Enter Facebook.

LifeLog, meanwhile, was ostensibly shut down. But this was not the first nor the last time that a project of this magnitude would be proposed.

In a 1945 article for The Atlantic, Vannevar Bush who, the reader will recall, directed the US Army’s psychological operations during World War II, discussed his hypothetical project, The Memex, as a device “in which an individual stores all his books, records and communications, and which is mechanised so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility.”

In immortalising people’s lives, it was hoped that LifeLog would eventually contribute to the emerging field of artificial intelligence (AI), that would one day think just like a human, intersecting with another DARPA backed project – the Personal Assistant That Learns (PAL) – a cognitive computing system designed to make military decision-making more efficient, which was eventually spun-off as Siri, the virtual assistant on Apple’s operating system, present in the homes of 1 billion unsuspecting people.

But LifeLog is just one part of the story. There was another DARPA program that also ‘disappeared’ one year before Facebook made its debut. Often cited as the precursor to Facebook, the Information Awareness Office (IAO) brought together several DARPA surveillance and information technology projects including MDDS which provided Google’s seed funding.

The stated aim of the IAO was to gather and store the personal information of every US citizen, including their personal emails, social networks, lifestyles, credit card records, phone calls, medical records, without, of course, the need for a search warrant.

This information would funnel back to intelligence agencies, under the guise of predicting and preventing terrorist incidents before they happened. Reminiscent of Project Camelot’s early warning radar system for left wing revolutionaries.

Despite the government, apparently, abandoning their gambit for total information awareness over ordinary Americans, the core of the project survived.

I draw your attention to Palantir, the spooky data analytics firm founded by Facebook’s board member, Peter Thiel.

Portrayed as science fiction in the firm Minority Report, Palantir’s predictive policing analytics have been deployed extensively against insurgents in Iraq and by police departments in the US.

The encroachment of the CIA into the public sphere has been happening since the 1960’s, when the US imported decades of counterinsurgency from the soviet satellites to tackle the anti-war and civil rights movements.

This was ramped up in the wake of 9/11 and now, through the backdoor of COVID-19 total information awareness, is coming home to roost, as China’s social credits system has been implemented on the back of the Green Pass.

Before anti-vaxxers and conspiracy theorists, you had civil rights and anti-war activists. The ideology guiding dissent may have changed, but the military tactics used to counter it remain the same.

Part 2: The War is Over, The Good Guys Lost

If insurgency is defined as an organised political struggle by a hostile minority attempting to seize power through revolutionary means, then counterinsurgency is the military doctrine historically used against non-state actors, that sets out to infiltrate and eradicate those movements.

Unlike conventional soldiers, insurgents are considered dangerous not because of their physical presence on the battlefield, but because of their ideology.

As David Galula, a French commander who was an expert in counterinsurgency warfare during the Algerian War, emphasised: “In any situation, whatever the cause, there will be an active minority for the cause, a neutral majority, and an active minority against the cause. The technique of power consists in relying on the favourable minority in order to rally the neutral majority and to neutralise or eliminate the hostile minority.”

Over time, however, the intelligence state lost touch with reality, as the focus of its counterinsurgency programs shifted from foreign to domestic populations, from national security risks to ordinary citizens -particularly in the wake of 9/11, when the NSA and its British counterpart, GCHQ, began mapping out the Internet.

Thanks to Edward Snowden’s revelations in 2013, we now know that the NSA were collecting 200 billion pieces of data every month, including the cell phone records, emails, web searches and live chats of more than 200 million ordinary Americans. This was extracted from the world’s largest internet companies via a lesser-known data-mining program called Prism.

There’s another name for this, and it’s total information awareness, the highest attainment of a paranoid state seeking absolute control over its population. What ceases to be worth the candle is that people’s right to privacy is enshrined under the US Constitution’s fourth amendment.

Few understand how lockdowns are ripples on these troubled waters. Decades of counterinsurgency waged against one subset of society, branded insurgents for their Marxist ideals, has, over time, shifted to anyone holding anti-establishment views. The predictive policing of track and trace and the theory of asymptomatic transmission are the unwelcome repercussions of the intelligence state seeking total information awareness over its citizens.

Throughout COVID-19, anyone audacious enough to want to think for themselves or do their own research has had a target painted on their back. But according to the EU, one third of Europe is unvaccinated. This correlates precisely with David Galula’s theory of counterinsurgency, that suggests one third of society is the active minority ‘against the cause,’ who must be neutralised or eliminated.

And for good reason. People are within sniffing distance of mobilising popular support from the neutral majority and toppling the house of cards. What follows is a protracted campaign by the establishment to neutralise the opposition.

It was not so long ago that journalists were called muckrakers, for digging up dirt on Robber Barons who, overtime, learned how to throw muck back, using smear and innuendo, such as ‘conspiracy theorist’, ‘anti-vaxxer’ and ‘right-wing extremist.’

When Domestic Populations Become the Battlefield

The use of counterinsurgency in the UK goes back to colonial India in the 1800s. According to historians, this was the first time the British government used methods of repression and social control against indigenous communities who were audacious enough to want to liberate their homeland from imperialist rule.

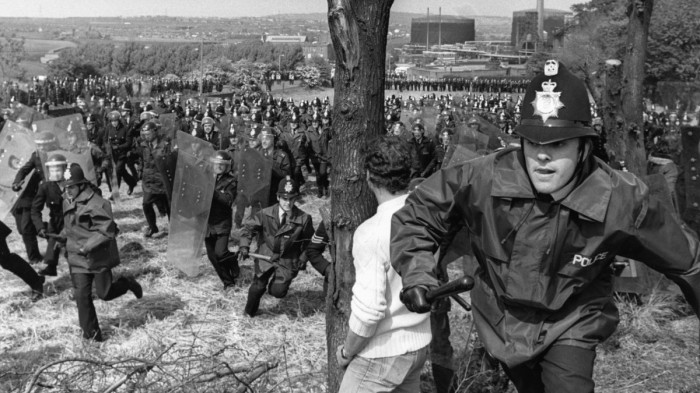

Counterinsurgency was used extensively during The Troubles in Northern Ireland against another anti-imperialist faction, also looking to liberate their homeland from The Crown. Much of the lessons learned in Northern Ireland were later transferred into the everyday policing and criminal justice policies of mainland Britain. And it wasn’t just dissenters who were targeted by these operations, it was anyone with left wing ideals, particularly trade unionists who, it could be argued, were conspiring with the Kremlin to overthrow parliamentary democracy.

Decades of infiltration has recalibrated the left into genuflections of establishment interests

I draw your attention to the spying and dirty tricks operations against the 1980s miners’ strike. This continued right up until 2012, when the police and intelligence communities were implicated in a plot to blacklist construction industry workers deemed troublesome for their union views.

The existence of a secret blacklist was first exposed in 2009, when investigators from the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) raided an unassuming office in Droitwich, Worcestershire, and discovered an extensive database used by construction firms to vet and ultimately blacklist workers belonging to trade unions. More than 40 construction firms, including Balfour Beatty and Sir Robert McAlpine, had been funding the confidential database and keeping people out of work for many years.

If you want to know what happened to the left, look no further than Project Camelot’s early warning radar system for left wing revolutionaries. Decades of infiltration has recalibrated the left into genuflections of establishment interests.

It was the unions who scuppered the easing of lockdowns in the UK and consistently called on the Department of Education to postpone the reopening of schools. This is despite the impact which school closures had on marginalised families, who were statistically more at risk from the fallout of lockdowns, and supposedly represented by union interests.

From the infiltration of unions to the co-option of activism, a judge-led public enquiry in 2016 revealed 144 undercover police operations had infiltrated and spied on more than 1,000 political groups in long term deployments since 1968. With covert spymasters rising in the ranks to hold influential leadership positions, guiding policy and strategy, and in some cases, radicalising those movements from within to damage their reputation and weaken public support.

We also need to talk about big philanthropy. George Soros’ Open Foundation is the largest global donor to the twenty-first century’s equivalent of activist groups. The agitprop used in the former Soviet Union evolved, over time, into the masthead of Extinction Rebellion, a motley crew of ‘eco-warriors’ courted by high profile financial donors and aligned ideologically with the very multinational energy corporations they are supposedly at odds with. This climate agenda came out of the UN, organiser of COP20, for what reason ER had to protest the event is anyone’s guess.

ER doner, George Soros, is also a seed investor in Avaaz, often cited as the world’s largest and most powerful online activist network. When the US was on the brink of insurrection, following the first lockdown, Black Lives Matter entered the fray, not so much a grassroots movement, but a proxy for the Democrats to essentially redirect the public’s outrage against lockdowns into the wrong, establishment-endorsed cause.

Counterinsurgency in the US

In the US, COINTELPRO was a series of illegal operations conducted by the FBI between 1956 and 1971, to disrupt, discredit and neutralise anyone considered a threat to national security. In the loosest possible definition, this included members of the Women’s Liberation Movement and even the Boy Scouts of America.

And it wasn’t just the customary wiretapping, infiltration and media manipulation: the FBI committed blackmail and murder.

Take, for example, the infamous forced suicide letter addressed to Martin Luther King that threatened to release a sex tape of the civil rights leaders’ extramarital activities, unless he took his own life. Consider also the FBI’s assassination of Black Panther Party chairman Fred Hampton.

In the 1960’s a Washington Post exposé by army intelligence whistle-blower Christopher Pyle revealed a massive surveillance operation run by the Army, called CONUS Intel, involving thousands of undercover military agents infiltrating and spying on virtually everybody active in what they deemed ‘civil disturbances.’ It turns out that many of those targeted had done nothing even remotely subversive, unless you consider attending a left-wing college presentation, or church meeting, revolutionary.

These programs came to a head in the 1970’s, when an investigation by the US Senate, conducted by the Church Committee, uncovered decades of serious, systemic abuse by the CIA. This included intercepting the mail and eavesdropping on the telephone calls of civil rights and anti-war leaders over two decades. As if predicting the internet as an instrument for mass surveillance, Senator Frank Church warned that the NSA’s capabilities could “at any time could be turned around on the American people.”

And turned around they were.

USAGM

Before the internet, the deployment of PSYOPS was limited to legacy media and permitted only on foreign soil. But that all changed in 2013, when the government granted themselves permission to target ordinary Americans.

Conceived at the end of the cold war as the Broadcasting Board of Governors, USAGM is a lesser-known government agency charged with broadcasting thousands of weekly hours of US propaganda to foreign audiences, that has played a major role in pushing pro-American stories to former Soviet Bloc countries ever since Perestroika.

Ostensibly concerned with maintaining US interests abroad, USAGM has also been the primary funder of the Tor Project since inception. Tor, also known as The Onion Browser, is the mainstay of encrypted, anonymous search used by activists, hackers, and the anonymous community, if you can get your head around the fact that the confidential internet activity of anarchists has been framed by a PSYOP since the get-go.

For decades an anti-propaganda law, known as the Smith-Mundt Act, made it illegal for the government to conduct PSYOPS against US citizens. But that all changed in 2013 when the National Defence Authorization Act repealed that law and granted USAGM a licence to broadcast pro-government propaganda inside the United States.

To what extent US citizens are being targeted by propaganda is anyone’s guess, since PSYOPS largely take place online, where it’s difficult to distinguish between foreign and domestic audiences.

What we do know is that in 2009 the military budget for winning hearts and minds at home and abroad had grown by 63% to $4.7 billion annually. At that time the Pentagon accounted for more than half the Federal Government’s $1 billion PR Budget.

An Associated Press (AP) investigation in 2016 revealed that the Pentagon employed a staggering 40% of the 5,000 working in the Federal Government’s PR machines, with the Department of Defence, far and wide, the largest and most expensive PR operation of the United States government, spending more money on public relations than all other departments combined.

Things are not so different in the UK.

During COVID-19 the British government became the biggest national advertiser. Even tick tock and snapchat were deployed by the Scottish government to push COVID PSYOPS to children.

Last year Boris Johnson announced record defence spending for an artificial intelligence agency and the creation of a national cyber force. That’s a group of militarised computer hackers to conduct offensive operations.

Offensive operations against whom, you might ask.

Britain was not at war, but in an article for the Daily Mail last year, Britain’s top counter terrorism officer, Neil Basu confirmed that the UK was waging an ideological war against anti vaccination conspiracy theorists. Ideological wars of this nature typically take place online, where much of the government’s military budget was being spent.

Since the vaccine roll-out there has been a protracted effort to paint the 33% of British citizens who have a problem with lockdowns and vaccine mandates, as violent extremists, with one member of the commentariat drawing parallels with US-style militias.

It doesn’t take a genius to see where this is heading.

The Facebook’s-Intelligence-Harvard Connection

Consistent with the opaque nature of Facebook’s origins, shortly after its launch in 2014 co-founders Mark Zuckerberg and Dustin Moskovitz brought Napster founder Sean Parker on board. At the age of 16, Parker hacked into the network of a Fortune 500 company and was later arrested and charged by the FBI. Around this time Parker was recruited by the CIA.

To what end, we don’t know.

What we do know is that Parker brought Peter Thiel to Facebook as its first outside investor. Thiel, who remains on Facebook’s board, also sits on the Steering Committee of globalist think tank, the Bilderberg Group. As previously stated, Thiel is the founder of Palantir, the spooky intelligence firm pretending to be a private company.

The CIA would join the FBI, DoD and NSA in becoming a Palantir customer in 2005, later acquiring an equity stake in the firm through their venture capital arm, In-Q-Tel. At the time of his first meetings with Facebook, Theil had been working on resurrecting several controversial DARPA programs.

Which begs the question: with intelligence assets embedded in Facebook’s management structure from the get-go, is everything as it seems at 1 Hacker Way?

According to Lauren Smith, writing for Wrong Kind of Green: “Some of Facebook’s allure to users is that Mark Zuckerberg and his friends started the company from a Harvard dorm room and that he remains the chairman and chief operating officer. If he didn’t exist, he would need to be invented by Facebook’s marketing department.”

By the same token, if Facebook didn’t exist it would need to be invented by the Pentagon.

To achieve this, you would need to embed government officials in Facebook’s leadership and governance. Cherry picking your candidates from, say, the US Department of Treasury, and launching the platform from an academic institution, Harvard University, for example.

According to the official record, Zuckerberg built the first version of Facebook at Harvard in 2004. Like J.C.R Licklider before him, he was a psychology major.

Harvard’s president at that time was economist Lawrence Summers, a career public servant who served as chief economist at the World Bank, was secretary of the treasury under the Clinton administration and 8th director of the National Economic Council.

Now here’s where it gets interesting. Summers’ protégée, Sheryl Sandberg, has been Facebook’s COO since 2008. Sandberg was at the dials during the Cambridge Analytica scandal, and predictably, manages Facebook’s Washington relationships. Before Facebook, Sandberg was chief of staff at the Treasury under Summers and began her career as an economist, also under Summer, at the World Bank.

Another Summers-Harvard-Treasury connection is Facebook’s Board Member, Nancy Killefer, who served under Summers as CFO at the Treasury Department.

It doesn’t end there. Facebook’s chief business officer Marne Levine also served under Summers at the Department of Treasury, National Economic Council and Harvard University.

The CIA connection is Robert M. Kimmet. According to West Point, Kimmet “has contributed significantly to our nation’s security…seamlessly blending the roles of soldier, statesman and businessman”. In addition to serving on Facebook’s board of directors, Kimmet is a national security adviser to the CIA, and the recipient of the CIA Director’s Award.

The icing on the cake, however, is former DAPRA Director, Regina Dugan, who joined Facebook’s hardware lab, Building 8, in 2016, to roll out a number of mysterious DARPA funded-projects that would hack people’s minds with brain-computer interfaces.

Dugan currently serves as CEO of Wellcome Leap, a technology spin-off of the world’s most powerful health foundation, concerned with the development of Artificial Intelligence (AI), including transdermal vaccines. Wellcome Leap brings DARPA’s military-intelligence innovation to “the most pressing global health challenges of our time,” called COVID-19.

Connecting the dots: Wellcome Leap was launched at the World Economic Forum, with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Its founder is Jeremy Ferrar, former SAGE member, long-time collaborator of Chris Witty and Neil Ferguson and the patsy taking the rap for the Wuhan leak cover-up story.

George Carlin wasn’t joking when he said: ‘it’s one big club, and you’re not in it.’

As luck would have it, just before Duggan’s arrival at Facebook, the social media giant orchestrated the controversial mood manipulation PSYOP, known as the Social Contagion Study. The experiment would anticipate the role social media went on to play during the pandemic.

In the study, Facebook manipulated the posts of 700,000 unsuspecting users to determine the extent to which emotional states can be transmitted across social media. To achieve this, they altered the news feed content of users to control the number of posts that contained positive or negative charged emotions.

As you would expect, the findings of the study revealed that negative feeds caused users to make negative posts, whereas positive feeds resulted in users making positive posts. In other words, Facebook is not only a fertile ground for emotional manipulation, but emotions can also be contagious across its networks.

Once we understand this, it becomes clear how fear of a disease, which predominantly targeted people beyond life expectancy with multiple comorbidities who were dying anyway, spread like wildfire in the wake of the Wuhan Virus. In locking down the UK, Boris Johnson warned the British public that we would all lose family members to the disease. When nothing could be further from the truth.

The pandemic largely happened in the flawed doomsday modelling of epidemiologists, it happened across the corporate media, and it happened on social media platforms like Facebook. It wasn’t so much a pandemic, but the social contagion experiment playing out in real time.

Politicians acquire impunity from public scrutiny and an entire nation is kept under house arrest

But there was more than just social media manipulating our emotional states: fear, shame, and scapegoating were rife, as the British government deployed behavioural economics to, essentially, nudge the public towards compliance.

Launched under David Cameron’s Government, the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT), (affectionately known as the Nudge Unit), are a team of crack psychologists and career civil servants tasked with positively influencing appropriate behaviour with tiny changes.

But according to whose measure of appropriate behaviour, exactly?

A clue lies in the fact that BIT was directed by Sir Mark Sedwill during the first lockdown. He’s one of Britain’s most senior national security advisors with links to MI5 and MI6.

That’s an intelligence operative ruling by psychological manipulation, though we are led to believe that, in a democracy, government is an agency of the people and parliament is given force of law by the will of the people.

But what happens when our consent is manipulated by those in power?

One consequence is that the foxes take charge of the chicken coop. Another is that we begin to see drastic changes to the constitutional landscape. Politicians acquire impunity from public scrutiny and an entire nation is kept under house arrest.

But this demonisation of the masses is also the backwash of a protracted counterinsurgency crusade waged on ordinary people. When the Berlin wall came down in the nineties and decades of counterinsurgency was rendered obsolete, the battlelines moved from East to the West, from the Soviets to the lower orders of society.

The mythos of communist infiltration, that gave rise to the threat of terrorism, is the ancestor of today’s biosecurity state. A government that tightens its grip, using fear of a common enemy, will find no shortage of common enemies, to continue tightening its grip.

Conclusions

Strong-arming the world’s population under the rubric of biosecurity would not have been possible without the internet, and if the expulsion of the military and intelligence community from academic institutions in the 1960’s had not resulted in the creation of Silicon Valley, they would not have acquired total information awareness, the precursor to the Green Pass.

But this formidable goal also caused the US to morph into the opponent it had been fighting during the cold war, as predicted by public intellectuals in the 1960s.

And so, with an annual budget of $750 billion and 23,000 military and civilian personnel in their employment, the Pentagon failed to denounce what many armchair researchers called out in the early days of the pandemic. That a global coup was underway was patently obvious, as crisis actors played dead in Wuhan, China.

Instead, those charged with protecting the west from Soviet-style putsch failed to apprehend it happening right under their noses. It’s not so much that they were caught with their trousers down, it’s that they aided and abetted the coop. Years of fighting a statist, expansionist adversary, caused the intelligence state to mutate into their nemesis, namely China.

It is uncanny that the country with the worst human rights record on earth became the global pacemaker for lockdowns, as western democracies exonerated their existential threat and bowed to China’s distinct brand of tyranny.

As a result, the big tech data analytics pioneered by Silicon Valley luminaries, road tested in China, finally landed on the shorelines of western democracies.

Another story entirely is the infiltration of sovereign nation states by the United Nations, whose special agency, the WHO, sparked the events that would lead to the fall of the West.

In an ironic twist of fate, the intelligence state created at the end of world war II, under the National Security Act, conceived the very corporations that would bring about the end of constitutional democracy.

Nowadays, it doesn’t matter if you’re in the dusty slew of a Calcutta slum or enjoying pristine views over Central Park, everyone is subject to the same scrutiny and surveillance, policed by the same community standards, manipulated by the same algorithms, and indexed by the same intelligence agencies.

No matter where you are, Silicon Valley is limiting what information you can see, share, communicate and learn from online. They are raising your kids, shaping your worldview and in the wake of COVID-19 and climate change, they have assumed the role of science administrator.

Founded on the principles of freedom of expression and heralded as a liberating new frontier for humanity, the internet has criminalised free speech, divorced it from our nature and ensnared us under a dragnet of surveillance.

But above all else, cyberspace has bought into existence a substructure of reality that is cannibalising the five-sensory world, while forcing humanity to embark on the greatest exodus in human history, from the tangible world to the digital nexus, from our real lives to the metaverse.

As Goethe’s quote goes: ‘None are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free.’ Namely, anyone still looking through rose-tinted lenses in the digital age, oblivious to the fact they are victims of systematic addiction.

The bread and circuses of the internet influences the same dopamine rewards centres and neural circuitry motivators as slot machines, cigarettes, and cocaine, as was originally intended by psychologists like JCR Licklider, at the helm of this new technology that would exploit basic vulnerabilities in the human psyche.

And as we descend further into the maelstrom of the digital age, the algorithms will get smarter, the psychological drivers will become more persuasive and digital rubric will become more real. Until eventually we will lose touch with reality altogether.

But don’t worry, this war of attrition is happening in conjunction with the roll out of new software and devices, and most will be too busy building their digital avatars or dissenting on social media to know any better.

Author

Dustin Broadbery is a writer and researcher based in London who has been writing about the New Normal these past two years, particularly the ethical and legal issues around lockdowns and mandates, the history and roadmap to today’s biosecurity state, and the key players and institutions involved in the globalised takeover of our commons. Aside from COVID-19, Dustin writes about the intelligence state, big tech surveillance, big philanthropy, activism and human rights. You can find his work at https://www.thecogent.org/ Or follow him on twitter @TheCogent1

![]() Please help keep us afloat. Donate here

Please help keep us afloat. Donate here